Chapter 11: Shaping Voting Outcomes

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 and subsequent amendments addressed inequities that disfranchising laws (1890-1908) enacted and perpetuated in the American South. It did not end efforts to shape the outcome of elections and raise new barriers to discourage some voters from casting their ballots. The advent of the digital age with its ever-more-accurate algorithms facilitated the drawing of district maps that advantaged one party over the other. The continued use of commission government inhibited the election of Black and Hispanic candidates in local elections. Voter ID laws raised issues regarding what constituted a valid ID by accepting for example a hunting license but not a student ID. Limiting the number of days for early voting and the number of polling stations made voting more difficult for some. After the 2020 election the widespread use of mail-in ballots produced new legislation in a number of states, particularly in the South, to limit access to this form of voting and limit the times and places for depositing ballots. The highly-charged rhetoric surrounding voting rights seems likely to continue long into the future.

Redistricting

The U.S. Constitution requires a decennial census for the purpose of determining representation in the House of Representatives. States also use population figures to apportion representation in their respective legislatures, and city and county governments likewise depend on federal population counts for political apportionment. Although the concept is simple and straight-forward, the practice is fraught with problems and conflicts.

Congressional Districts, 1845-2010.

(United States Congressional District Shapefiles, Jeffrey B. Lewis, UCLA.)

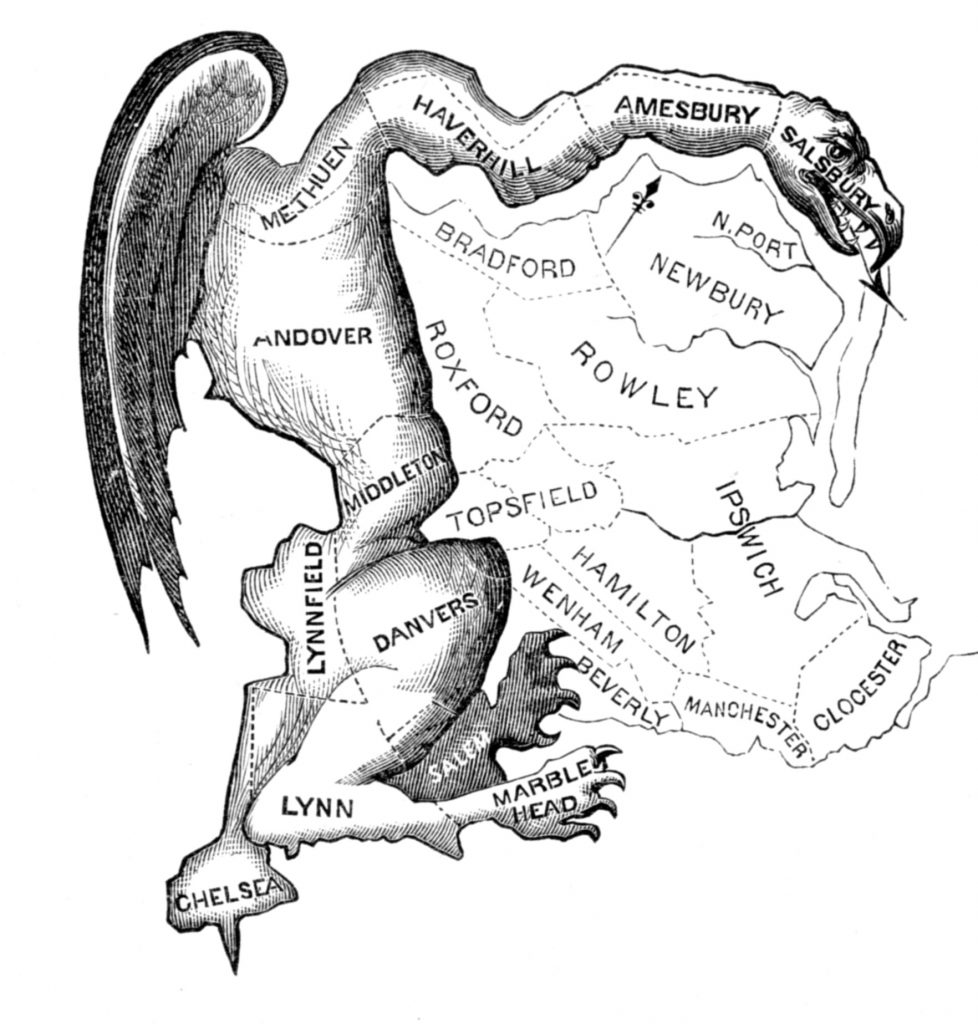

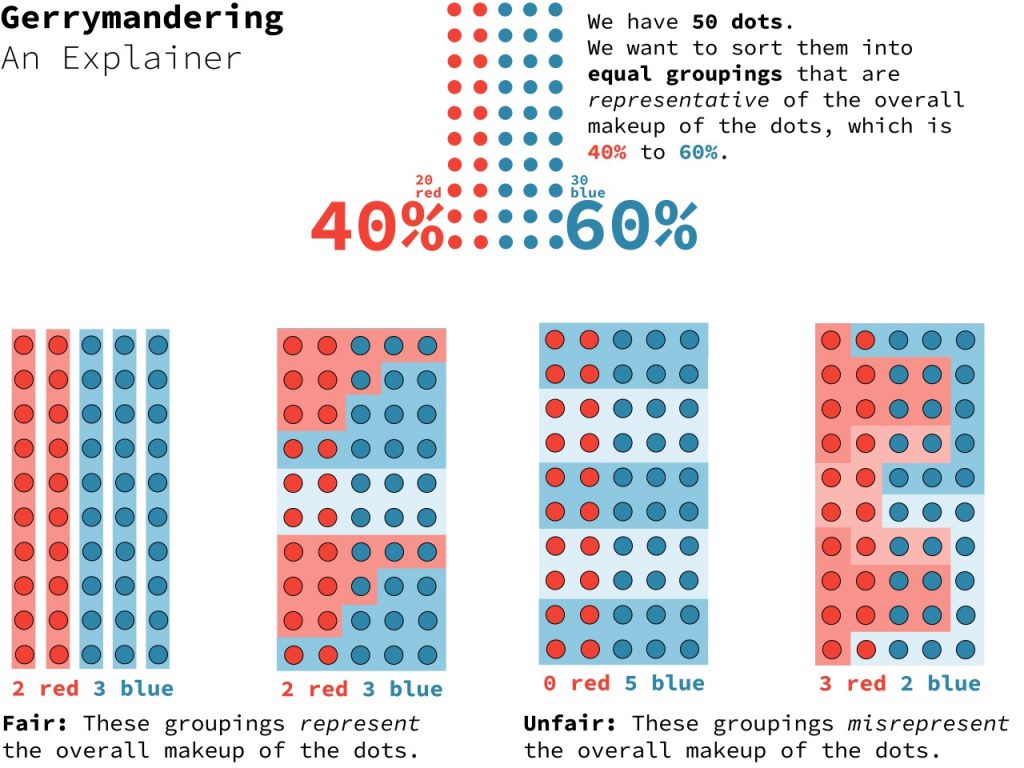

Gerrymandering

Gerrymander: To divide or arrange (a territorial unit) into election districts in a way that gives one political party an unfair advantage. Merriam-Webster.

Although the Voting Rights Act of 1965 prohibits redistricting for the purpose of reducing the political influence by a racial minority, gerrymandering along racial lines has been used both to decrease and increase minority representation in state governments and congressional delegations. In 1971 the Department of Justice stopped Mississippi’s attempt to force African American citizens to re-register to vote based on redrawn district boundaries. However, by 1981, under the Reagan Administration’s Department of Justice, Alabama successfully passed a bill purging the voting roles and requiring voters in three counties with predominantly African American populations to “reidentify” themselves by physically going to the courthouse. African American registration subsequently dropped by 43 percent.

Types of Gerrymandering Tactics

Cracking divides a community into multiple districts. This tactic was often used to ensure that African American politicians would not be elected by predominantly African American voters. Although the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was somewhat successful in banning racially motivated cracking, the tactic is still used to split communities for partisan gain.

Packing combines several communities into a single district to minimize their number of representatives. When racially motivated, this is known as bleaching. In 1990 Florida’s 3rd Congressional District, which included Orlando, Gainesville and Jacksonville, combined African American neighborhoods from all three cities to form a single district.

Hijacking pins two incumbents against one another by combining their districts.

Kidnapping moves an incumbent’s home address into another district.

Failure to redistrict is a tactic used by states in which they choose not to reapportion according to the federal census to provide for districts of substantially equal population despite large population shifts across districts within the state. This strategy was employed in support of racial segregation by a group of 20 Democratic legislators from rural areas of North and Central Florida, known as the Pork Chop Gang, from the 1930s through the 1970s.

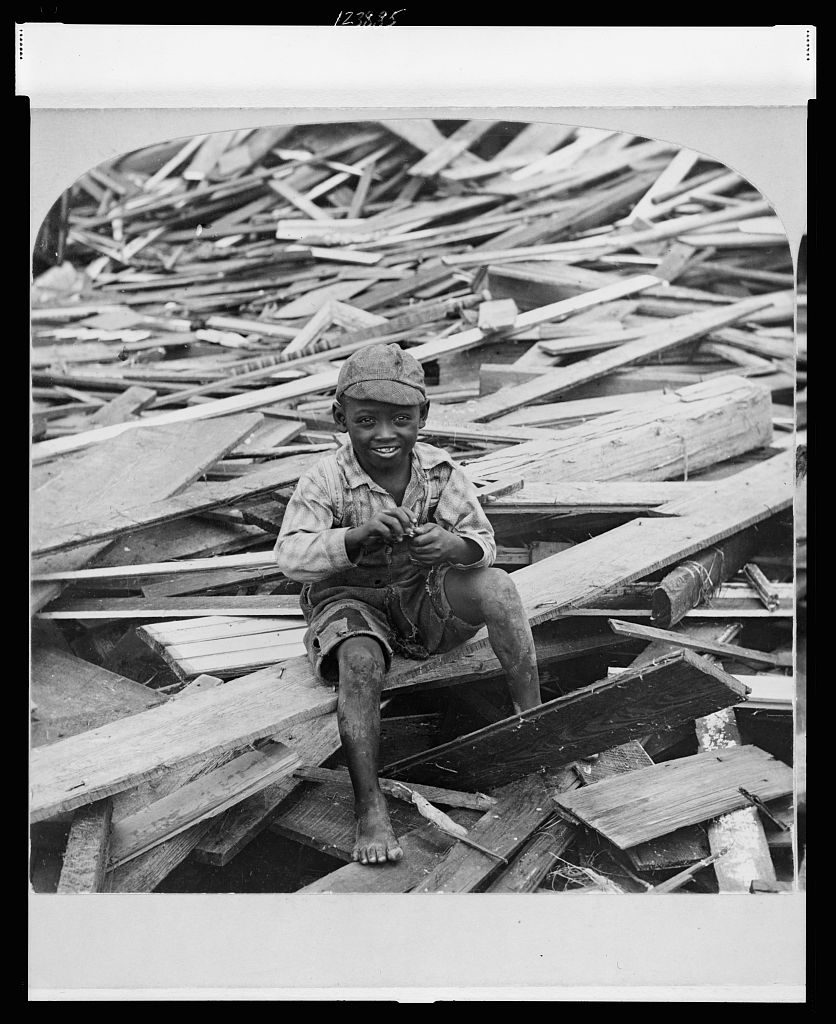

Commission Government

The Galveston Hurricane of 1900 was the deadliest natural disaster in United States history, with most deaths occurring in and around Galveston, Texas. The storm left homeless approximately 10,000 of the city’s 38,000 residents. Prompted by fears that the existing city council would be unable to handle rebuilding the city, the Galveston city government reorganized into a commission government in 1901. The constitutionality of this was tested and confirmed, and by 1920 around 500 cities across the US had adopted the form of government.

Black boy sitting on debris in the wake of the 1900 hurricane in Galveston, Texas.

(Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.)

A commission form of city government is made up of a small group of commissioners responsible for individual agencies, who are elected on a plurality-at-large voting basis. This forces area-wide elections rather than specific district representation. As a consequence, Blacks were not elected to city council in places like Mobile, Alabama. Although they made up 1/3 of the population in 1980, there had not been a single Black elected official since 1911, the last time elections had been organized by district rather than citywide. A Black candidate could not be elected without significant White support.

The Mobile National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) sued, charging that the city’s government violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which put the burden of proof on plaintiffs to show that a voting change was discriminatory and could be used to challenge electoral structures adopted before 1965. When the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals found that the city’s election system discriminated against Blacks, violating the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments to the Constitution, Mobile appealed to the US Supreme Court. The Court ruled that racial intent had to be proven and since there was no indication that intent was racial, there was no case. Justice Potter Stewart wrote, “Racially discriminatory motivation is a necessary ingredient of a Fifteenth Amendment violation. The Amendment does not entail the right to have Negro candidates elected but prohibits only purposefully discriminatory denial or abridgment by government of the freedom to vote ‘on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.’” Since intentional discrimination, which had never before been required under the Voting Rights Act, was virtually impossible to prove, the decision represented the most significant setback for the VRA since its passage in 1965.

Along with some members of Congress, President Ronald Reagan endorsed the view that those who filed civil lawsuits alleging a denial of voting rights should be required to prove a discriminatory purpose, not merely the results of effects of discrimination. Pressured by organizations such as The Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, the NAACP, and the National Education Association (NEA), a compromise was reached when Senator Robert Dole proposed language disclaiming that a results test would require proportional representation. This version passed by a landslide in both the House and Senate, and President Reagan signed it into law on June 29, 1982, amending Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act on general prohibition of discriminatory voting laws to overturn the Mobile v. Bolden decision. Though the Voting Rights Act had been renewed twice before by Presidents Nixon and Ford, the 1982 reauthorization made Section 2 of the VRA permanent.

Current Voting Controversies

Voter registration restrictions: One of the most common forms of voter suppression is restricting the terms and requirements of registration, including requiring proof of citizenship or identification, limiting the window of time in which voters can register, or burdensome obstacles for voter registration drives.

Limiting the number of early voting days: Since 2011 politicians have led efforts to reduce early voting for partisan gain, leading to longer lines and fewer voters. In 2012 Florida reduced early voting days from 14 to 8. Seventy percent of Black voters in North Carolina voted early in 2008 and 2012. In 2012 Black voters in Ohio voted early at more than twice the rate of White voters.

Cutting down on the number of polling stations: Counties with larger minority populations have fewer polling sites and poll workers per voter. Between 2012 and 2016 voters in majority-minority urban counties lost an average of seven polling places and more than 200 poll workers. However, in more than 1,000 counties where over 90% of the population is White, residents lost an average of two polling locations and two workers in 2016.

Voter purges: This process can be used as a method of mass disenfranchisement, purging eligible voters for illegitimate reasons, based on inaccurate data, and often without adequate notice. A single voter purge can keep hundreds of thousands of people from voting. New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman revealed that 200,000 New York City voters had been illegally wiped off the rolls and prevented from voting in the 2016 Democratic presidential primary between Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton. A Daily News editorial called the primary “a disaster for voting rights and democracy – and a horrifying embarrassment for New York.”

Mail-in ballots: As election officials tried to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic during the 2020 presidential election, mail-in balloting received a large boost. Since then a number of states have limited open access to mailing ballots and placed restrictions on mail-in ballots.

(Mail-in ballot from Escambia County, Florida. Image courtesy of Florida Supervisors of Elections.)

Voter ID laws: Thirty-six states have identification requirements at the polls, seven of which have strict photo ID laws, under which voters must present one of a limited set of forms of government-issued photo ID to cast a ballot. What qualifies as valid ID is often in question. Some states consider a hunting license valid but not a student ID. Over 21 million citizens do not have qualifying government-issued photo identification, and these individuals are disproportionately voters of color. Twenty-five percent of voting-age Black Americans do not have a government-issued photo ID. Identification cards and other expenses required to obtain documents can be costly, disproportionately affecting those in lower-income communities. The travel required can also be challenging for people with disabilities, the elderly, and those living in rural areas.

Criminalization of the ballot box: Voter participation is discouraged in some states by the imposition of arbitrary requirements and harsh penalties on voters and poll workers who violate these rules. Lawmakers in Georgia have criminalized providing food and water to voters standing in line at the polls. Especially in communities of color, voting lines in Georgia are notoriously long. Voters in Texas have been arrested and given jail sentences for innocent mistakes made during the voting process. –

Campaign finance reform: Although money in politics predates the Supreme Court decision, Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, 558 U.S. 310 (2010), asserted that corporations are people and reversed century-old campaign finance restrictions, allowing a small group of wealthy donors and special interests to use unlimited dark money to influence elections through the creation of super PACs (political action committees). The decision has not only increased the cost of campaigns but has further tilted the political influence of wealthy donors, sustaining racial bias and reinforcing the racial wealth gap.

______________________________________________________________________________

Anderson, Carol. One Person, No Vote. New York: Bloomsbury, 2018.

Asip-Kneitschel, Stacey. “NYC purged 200,000 voters in 2016. It wasn’t a mistake.” City and State NY, November 8, 2018. https://www.cityandstateny.com/politics/2018/11/nyc-purged-200000-voters-in-2016-it-wasnt-a-mistake/177964/.

Baker v. Carr https://www.oyez.org/cases/1960/6

Ball, Howard. “Racial Vote Dilution: Impact of the Reagan DOJ and the Burger Court on the Voting Rights Act.” Publius 16, no. 4 (1986): 29-48. Accessed July 22, 2021. doi:10.2307/3330157.

Berman, Ari. Give Us the Ballot: The Modern Struggle for Voting Rights in America. New York : Picador/Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016.

“Block the Vote: How Politicians are Trying to Block Voters from the Ballot Box.” ACLU, August 18, 2021. https://www.aclu.org/news/civil-liberties/block-the-vote-voter-suppression-in-2020/.

“Cutting Early Voting is Voter Suppression.” ACLU, 2021. https://www.aclu.org/issues/voting-rights/cutting-early-voting-voter-suppression.

Evenwel v. Abbott https://www.oyez.org/cases/2015/14-940.

Johnson, Theodore R. “The New Voter Suppression.” Brennan Center for Justice, January 16, 2020. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/new-voter-suppression.

Lau, Tim. “Citizens United Explained.” Brennan Center for Justice, December 12, 2019. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/citizens-united-explained.

Lewis, Jeffrey, Brandon DeVine, and Lincoln Pritcher with Kenneth C. Martis. “United States Congressional District Shapefiles.” UCLA, 2013. https://cdmaps.polisci.ucla.edu/.

Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980).

Nichols, Mark. “Closed voting sites hit minority counties harder for busy mid-term elections.” USA Today, October 30, 2018. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/2018/10/30/midterm-elections-closed-voting-sites-impact-minority-voter-turnout/1774221002/.

O’Rourke, Timothy G. Constitutional and Statutory Challenges to Local At-Large Elections, 17 U. Rich. L. Rev. 39 (1982).

Available at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/lawreview/vol17/iss1/3.

Ostrow, Ashira Pelman. “One Person, One Weighted Vote.” Florida Law Review, 68, no. 6, November 2016: 1-43. https://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1340&context=flr

Pear, Robert. “Reagan Backs Voting Rights Act But Wants to Ease Requirements.” New York Times. November 7, 1981. https://www.nytimes.com/1981/11/07/us/reagan-backs-voting-rights-act-but-wants-to-ease-requirements.html. Accessed July 22, 2021.

Reynolds v. Sims https://www.oyez.org/cases/1963/23.

Sanders, Hank, and Frances M. Beal. “Black Scholar Interview with Hank Sanders: DEFENDING VOTING RIGHTS IN THE ALABAMA BLACK BELT.” The Black Scholar 17, no. 3 (1986): 25-34. Accessed July 22, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41067271.

“The ACLU and Citizens United.” ACLU, 2021. https://www.aclu.org/other/aclu-and-citizens-united.

“The Florida Senate.” Redistricting – The Florida Senate. Accessed July 26, 2021. https://www.flsenate.gov/session/redistricting.

Weiner, Rachel. “Florida early voting cuts survive.” Washington Post, September 24, 2012. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-politics/wp/2012/09/24/florida-early-voting-cuts-survive/.

Whitesides, John and Julia Harte. “Explainer: Why vote by mail triggered a partisan battle ahead of November’s election.” Reuters, April 14, 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-election-absentee-voting-explaine/explainer-why-vote-by-mail-triggered-a-partisan-battle-ahead-of-novembers-election-idUSKCN21W162.

Yee, Vivian. “Routine Voter Purge is Cited in Brooklyn Election Trouble.” New York Times, April 22, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/23/nyregion/routine-voter-purge-is-cited-in-brooklyn-election-trouble.html.