Chapter 3: Black Ocoee’s Economic Power

This section considers multiple dimensions of Black Ocoee’s economic power, including not only its economic leaders but the agricultural and domestic laborers who contributed wealth to the community. It also considers the social wealth of Black Ocoee, and examines the effects of larger national events, like World War I, on the town.

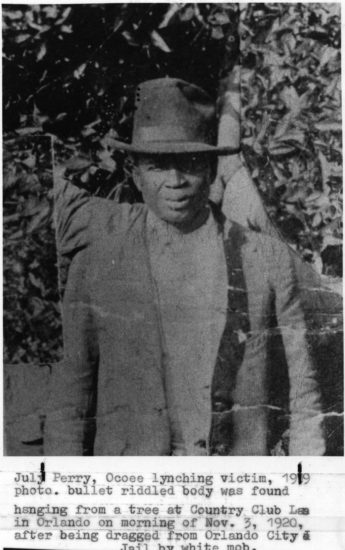

The economic power of Black Ocoee formed part of the social currents of the early twentieth century. Using census data, scholars have demonstrated that in 1900, the economic and education opportunities for Black communities remained much the same as it had in the nineteenth century— which is to say, incredibly low when compared to Whites. Black communities remained largely in the Deep South, tied to agricultural labor on lands they most often did not own. Some, like July Perry, Mose Norman, and Valentine Hightower, managed to move internally within the South and migrated to Florida where the prospect of better economic opportunity beckoned. In the decades between 1885, when the first Black migrants settled in Ocoee, to 1920, the year of the Massacre, Black women and men moved into the Central Florida region and contributed to its economic and social development.

Creating Generational Wealth: Five Black Families

“In Florida, the New Negro had grey hair.” -Paul Ortiz

Mose Norman

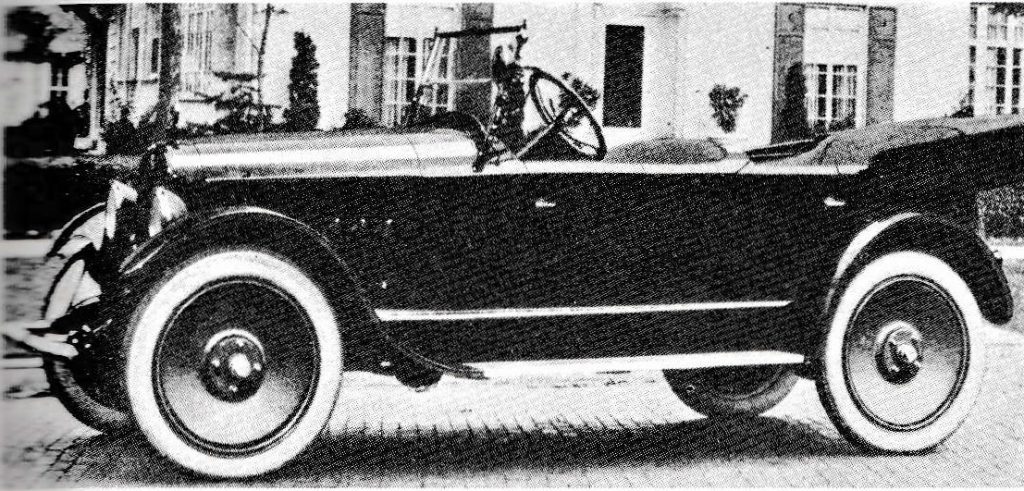

Born in 1861, Mose Norman migrated from South Carolina in the 1880s with July Perry and Valentine Hightower. He and his wife Elisa were criticized for engaging in the consumer economy that their hard work enabled. Norman owned a 100-acre orange grove that both Blacks and Whites reported as valued at $10,000. He drove a six-cylinder Columbia convertible like the one in the image. His “lavish lifestyle” engendered the wrath of many Whites who believed he defied the expectations for Blacks that were central to White supremacy. In the chaos of events on November 2-3, he escaped from Ocoee and migrated to New York where he died in 1949.

The importance of Mose Norman’s ownership of an automobile at the time of the Ocoee Massacre cannot be understated. The car, a Columbia Six, was a short-lived but respected, assembled marque in Detroit. Scholars of the history of transportation have suggested that Henry Ford’s Model T assembly-line production and higher wages after 1914 democratized auto ownership in the U.S. Indeed, the car became the singular manufacturing and consumer product of the 20th century. Norman’s choice of a Columbia Six challenged the hierarchical racial structure that defined southern social relations. Access to technology and high-end consumer goods defied expectations that modernity was for Whites only, with the role of Blacks limited to low wage, manual labor, primarily in agriculture. Such roles inhibited access to automobiles, particularly one as expensive as the Columbia Six.

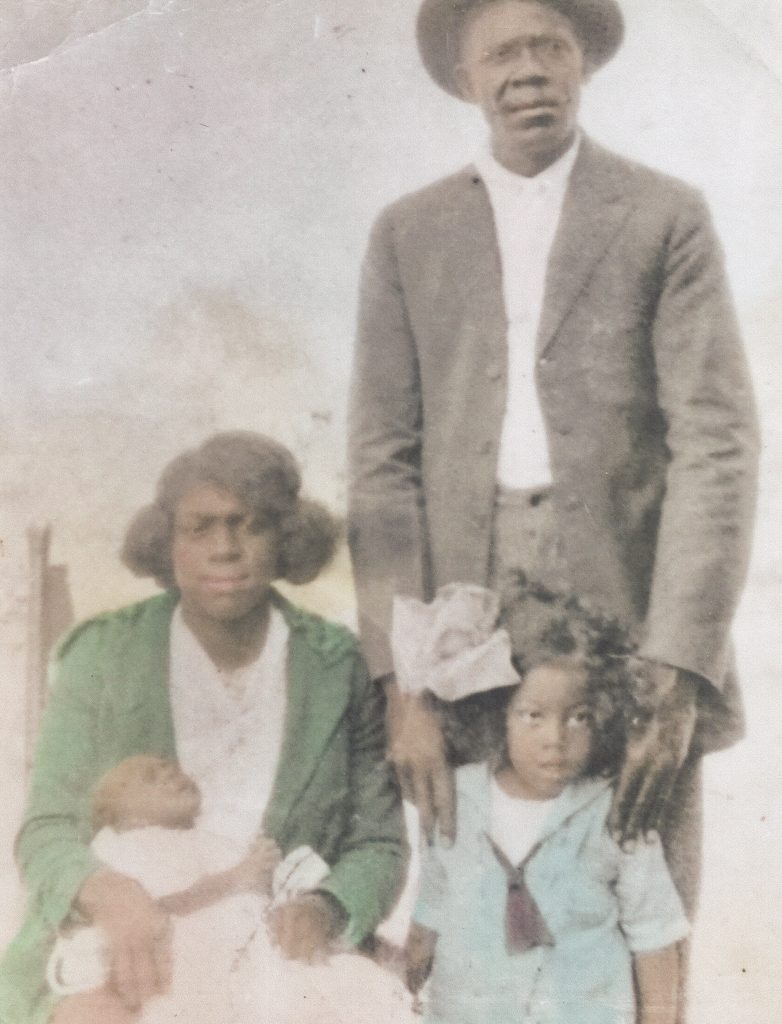

Julius “July” Perry

Julius “July” Perry (1868-1920) was one of the most prominent members of the Black Ocoee community. The 1910 U.S. Census lists Perry, his wife Estelle and six children at the residence: Coretha, Charlie, Clifford, Louise, Bessie, and Dolfus. Their property included a house and several barns and outbuildings and was located near Perry’s lifelong friends the Normans and the Valentines. Perry was a social, religious, and economic leader of the Black community. He was the person other members of the community sought out when they were in need or in trouble. He was a deacon in his church and an officer in the local Prince Hall Masonic lodge. Perry, along with Norman, controlled access to Black agricultural labor in Ocoee, a powerful position and one that earned the enmity of local Whites.

Valentine Hightower

Valentine Hightower was born in the mid-1860s in South Carolina. In 1885, Hightower and his friends, July Perry and Mose Norman, came to Central Florida and settled in what would become the small community of Ocoee. The 1885 Florida State Census records Hightower and Norman as occupants in the house of B.M. Sims, likely Bluford Sims, a Confederate veteran who had also recently arrived in the area and who gave the town its name. Valentine Hightower, Mose Norman, and July Perry became pillars of the Black community that developed over the next few decades.

John Wesley and Lucy Hickey

John Hickey was born March 1, 1871, in Moultrie, Georgia. Lucy Silonia Lott was born April 3, 1894, in Sneads, Florida. The couple had six children together in addition to his children from a previous marriage. The Hickey family was prosperous. John Hickey was industrious, working in the lumbering business, distilling turpentine, running a delivery business, and buying and selling property.

One of Hickey’s properties was a citrus grove in Apopka, which is where they resettled after they fled the Ocoee Massacre. He built a home in the grove along with several other smaller houses that he rented to migrant workers who came in to pick citrus or work on the muck. Their grandson, Robert Hickey, grew up in that home, not realizing how much the family had lost until he conducted his own research decades later. According to Robert Hickey his grandfather lost over a hundred acres, which he believed was more land lost than any other family as a result of the Ocoee Massacre.

“I think that it was quite an accomplishment. Slavery ended in 1865, and here we’re talking about 1920. 50 years or so later. A tremendous accomplishment by these African-American people to build an upstanding community, where most of them…weren’t lacking. They had some fellowship. A camaraderie amongst themselves. And they did well. They were thriving. And Mose [Norman] and July Perry. I think I read something about Mose had a real fancy automobile.” (Oral History, Robert Hickey, February 26, 2019.)

“And then to read about John Hickey and his holdings. There’s an area in Ocoee right now, they still sometimes refer to it as Hickey Subdivision. And it’s like three blocks or more where he had this property that he had divided up to more than 50 different parcels for sale. I don’t know if he was gonna sell it all or if he was going to do some development. But it seems like he had some grand plans. And that made me real proud…that he was thinking like that.” (Oral History, Robert Hickey, February 26, 2019.)

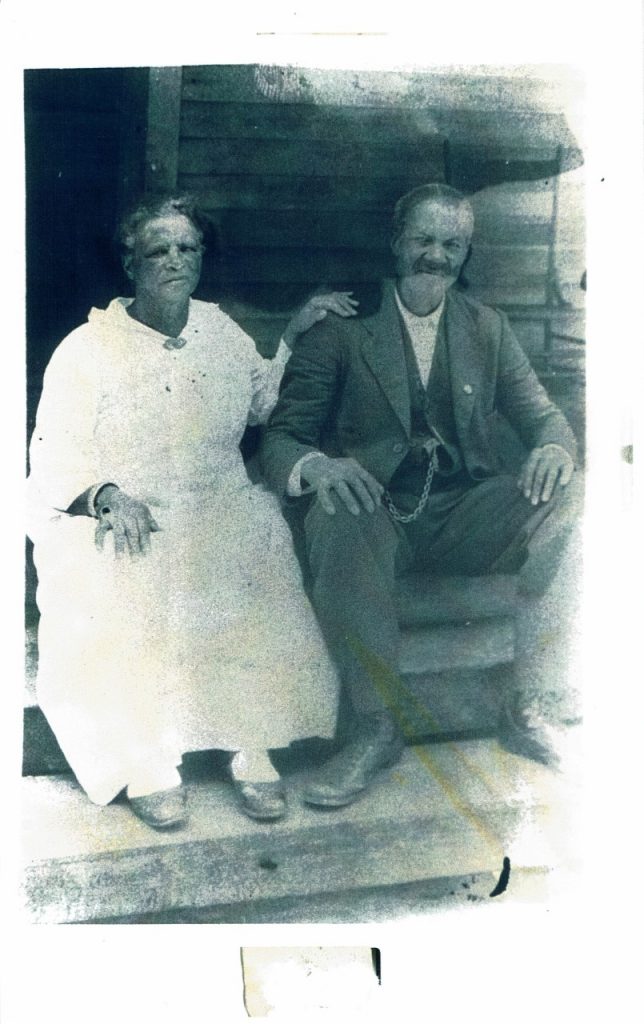

Jackson (Jack) and Annie Hamiter

Jackson (Jack) and Annie Hamiter were born in South Alabama; he was born in 1861 into slavery, but she was born during the Reconstruction Era. As the first generation of Black citizens, their story informs us about the possibilities and barriers Blacks faced in the New South. Initially they were sharecroppers in an agricultural system that provided few opportunities to advance economically. Toward the end of the 19th century, they moved to Ocoee with their three children, Rosa, Lafayette, and Hattie. They came to Florida because there were more opportunities to obtain productive land ownership and build generational wealth.

Black Labor in Ocoee

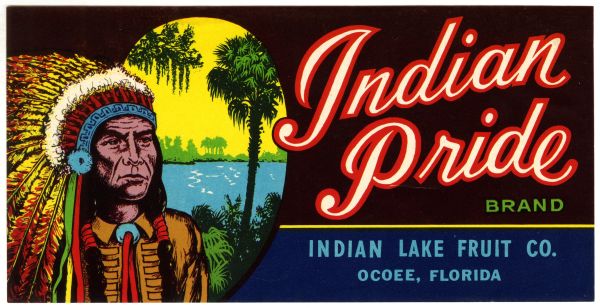

The trademark image of the Native American wearing a headdress and buckskin garment affirmed them as historical figures while simultaneously placing them outside the twentieth century. The logo fronted a Florida landscape of lake and palm trees which also exoticized and authenticated the brand as Florida fruit. (Image courtesy of Florida Memory.)

Grower’s Best Brand. ca. 1930. Brand Label. Growers Fruit and Produce Co., Ocoee, Florida., Ocoee, Florida, ca. 1930. (Image courtesy of Florida Memory.)

Labor Conflicts in the Groves, Fields, and Homes

Labor in the Ocoee area was controlled through White supremacy and the threat of racial violence. The national context of racial tension exacerbated the moment, but Florida had a long history of labor conflict and violence stretching back to the Reconstruction era.

Paul Ortiz claims that “The African-American working class provided the catalyst for social and political change in Florida by engaging in four years of heightened labor struggle beginning in 1916.” They did so through the Great Migration of labor from Florida to more promising cities in the North, by organizing Black unions, and by engaging in strikes against White employers. Examples of labor actions by Black workers included demands by domestic workers in St. Petersburg for wages of $3 per day, a strike by longshoremen in Key West, a strike by Black orange pickers in Crescent City for 10 cents per box, and demands by Black workers in Putnam County potato fields for higher wages.

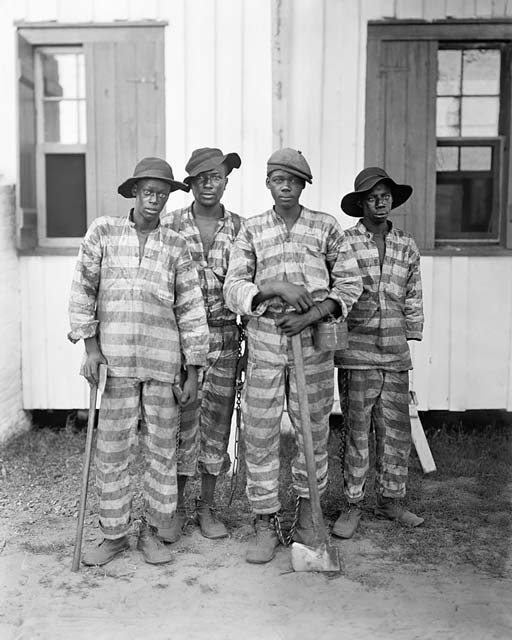

Convict Leasing

Local economic hegemony included “White business supremacy” in which capital and commerce exploited Black labor in various forms: sharecropping, low wages, and most notoriously through convict leasing. In the first decades of the twentieth century, sheriffs, justices of the peace, and judges arrested and convicted Blacks, often on minor offenses or offenses such as vagrancy that were applied only to Blacks, and sold their labor to mines, lumber and turpentine companies, and individual farmers. The use of this new forced labor system was considered “modern” and acceptable to planters and industrialists according to historian Alex Lichtenstein. Historian Vivien Miller estimated that Florida’s convict lease system was applied to 11,000 incarcerated individuals in Florida between 1889 and 1918.

Blackmon, Douglas, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Establishment of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II. New York City: Anchor Books: 2008.

Byrne, Jason. “Ocoee on Fire: The 1920 Election Day Massacre.” Medium, November 23, 2014. Accessed April 19, 2021. https://medium.com/florida-history/ocoee-on-fire-the-1920-election-day-massacre-38adbda9666e.

“Florida Deaths, 1877-1939.” Database with images, FamilySearch. Entry for Jannie Hightower in 1926. Accessed April 19, 2021. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FP3J-9VX.

“Florida Deaths, 1877-1939.” Database with images, FamilySearch. Entry for Valentine Hightower in 1932. Accessed April 19, 2021. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FPZJ-12Y.

“Florida Marriages, 1837-1974.” Database, FamilySearch. Entry for V.T. Hightower on April 1, 1893. Accessed April 19, 2021. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FW9K-C8V.

“Florida State Census, 1885.” Database with images, FamilySearch. Entry for Valentine Hightower in the house of BM Sims. NARA microfilm M845. Accessed April 19, 2021. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MNJZ-D4G.

Herring, Troy. “A Century Removed: Truth and Reconciliation of the 1920 Ocoee Massacre.” Orange Observer, October 28, 2020. Accessed April 19, 2021. https://www.orangeobserver.com/article/a-century-removed-truth-and-reconciliation-of-the-1920-ocoee-massacre.

Lichtenstein, Alex, Twice the Work of Free Labor: The Political Economy of Convict Labor in the New South. London: Verso, 1996.

Mancini, Matthew, One Dies, Get Another: Convict Leasing in the American South, 1866-1928. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1996.

Marchand, Roland, Advertising the American Dream: Making Way for Modernity, 1920-1940. Berkley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1985.

Miller, Vivien M., Crime, Sexual Violence, and Clemency: Florida’s Pardon Board and Penal System in the Progressive Era. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2000.

O’Barr, William M. Culture and the Ad: Exploring Otherness in the World of Advertising. Boulder, San Francisco, Oxford: Westview Press, 1994, 49-53.

Ortiz, Paul, “Eat Your Bread without Butter, but Pay Your Poll Tax!” in Charles M. Payne and Adam Green, eds, Time Longer Than Rope: A Century of African American Activism, 1850-1950. New York: New York University Press, 2003, 196-229.

Sellers, Sean and Gred Asbed, “The History and Evolution of Forced Labor in Florida Agriculture,” Race/Ethnicity: Multidisciplinary Global Contexts 5, no. 1 (Autumn 2011): 29-49.

Shofner, Jerrell H., “The Labor League of Jacksonville: A Negro Union and White Strikebreakers,” Florida Historical Quarterly 50, no. 3 (January 1973) 278-282.

“United States Census, 1900.” Database with images, FamilySearch. Entry for Valentine Hightower in Precincts 10-11, Ocoee, Apopka. NARA microfilm T623. Accessed April 19, 2021. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:M368-9QB.

“United States Census, 1910.” Database with images, FamilySearch. Entry for Valentine Hightower in Ocoee. NARA microfilm T624. Accessed April 19, 2021. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MVKV-WNL.

“United States Census, 1920.” Database with images, FamilySearch. Entry for Valentine Hightower in Ocoee. NARA microfilm T625. Accessed April 19, 2021. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MNB7-NHS.

Thirteenth Census of the United States taken in the year 1910, Volume 1, Population 1910: General Report and Analysis. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1915.

Telephone conversations with Patricia Whatley and Camilla Barnes, July 2020.