Chapter 10: Limiting the Right to Vote

The abolition of slavery through the 13th Amendment, the definition of citizenship with the 14th Amendment, and the creation of universal manhood suffrage with the 15th Amendment propelled the nation into a modern political economy but met strong resistance in the South. Political leaders, especially advocates for a new industrial, urban South put a “best face” on the abolition of slavery, claiming that abuses by the “few” ensured its demise. At the same time these proponents of the New South championed the Lost Cause mythology and worked tirelessly to create a penal system and a farm labor system that assured Black workers a lifetime of penury with few opportunities for advancement.

By the end of the 19th century, an expanding Black middle class threatened the very foundations of White Supremacy, particularly in the political arena as Black candidates continued to be elected to local, state, and national offices. In all southern states, White political stakeholders undertook efforts to disfranchise Black voters. Successful disfranchising laws prevented most Blacks from casting ballots but carefully incorporated language that did not use race as a distinction to avoid inciting investigations and action by the federal government. Disfranchisement took several forms including the use of violence and intimidation and the creation of laws establishing poll taxes, literacy tests, and separate ballot boxes. The Democratic Party used the new political reform, the primary, to eliminate Black voting. Finally, state legislatures frequently resorted to appointment to office of judges and sheriffs to prevent election of Black candidates to these positions.

Violence and Intimidation

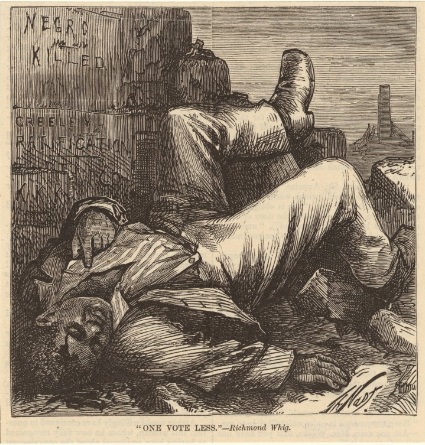

Violence was the first and last resort for denying Black citizens the right to vote. Beginning with the Reconstruction era, Black voters and officeholders faced threats, intimidation, and violence ranging from whippings and beatings to lynching. In 1872, the Richmond [Virginia] Whig published a graphic cartoon titled “One Vote Less” in which a Black man lies dead surrounded by the words and images meant to convey the election campaign between Republican candidates for the presidential nomination Ulysses Grant and Horace Greely. A similar cartoon could have been published during any political campaign between 1872 and 1965.

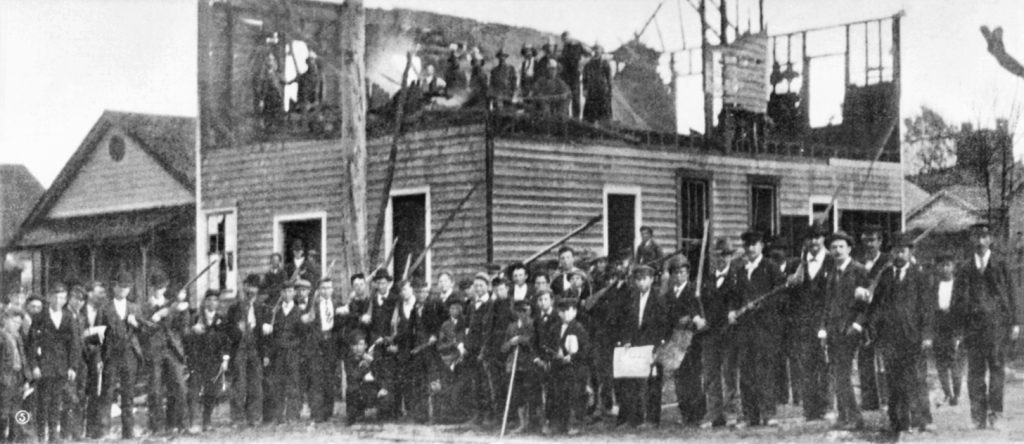

The Wilmington, North Carolina, insurrection in 1898 and the Ocoee Massacre of 1920 stand out as examples of violence against an entire community as a result of successful Black voting. In November 1898, White insurrectionists staged a coup to overthrow the duly elected fusion government of Wilmington and issued “A Declaration for White Supremacy.” In what historians labeled a coup, White insurrectionists targeted Black businesses, including the Black newspaper The Record for destruction. During the rampage Black-owned buildings were destroyed by fire and 14-30 Black citizens were killed. The image below shows the White insurrectionists posing in front of one of many buildings burned by the mob. (Image courtesy of New York Public Library.)

(Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.)

Creation of Disfranchising Laws, 1890-1906

In 1890 the State of Mississippi rewrote its constitution primarily to address voting and voting rights. Worried by the influence of Black voters, recent Populist calls for cross-party support for political reforms and a more activist federal government, and concerns about potential federal interference in southern elections, delegates to the constitutional convention sought to disfranchise Black voters without incurring federal congressional or judicial action. The so-called “Mississippi Model” succeeded beyond expectations. In 1898 the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the Mississippi Constitution in Williams v. Mississippi and every Southern state adopted similar disfranchising legislation in whole or in part. Although continuously protested by Black communities of voters and challenged repeatedly by lawyers associated with the NAACP, the collection of disfranchising laws remained in place from the late 19th century to 1965 and the passage of the Voting Rights Act.

Disfranchising Laws

Not every state adopted laws that utilized all the tactics listed here, but every Southern state passed one or more of the laws.

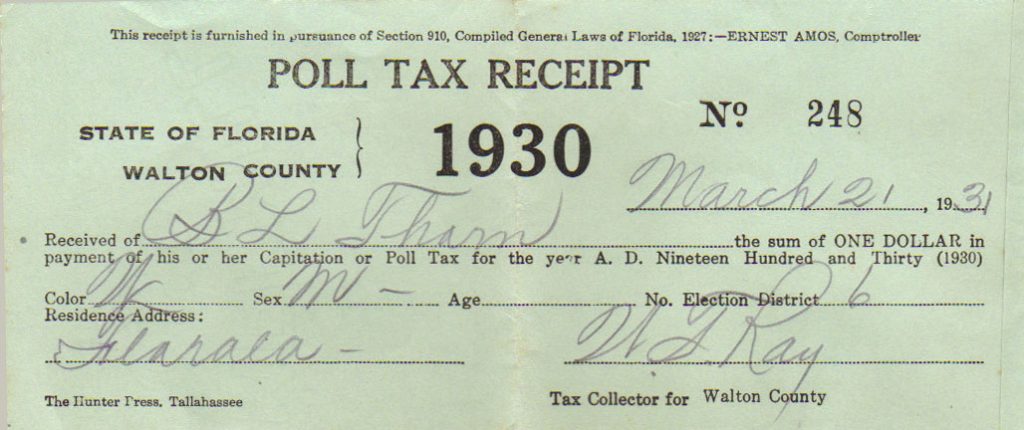

Poll Tax

This was, by far, the most popular disfranchising law. The State of Florida was the first state to authorize the collection of a poll tax in the 1885 state constitution and in 1889 the state legislature set the rate at $2.00. Although the sum was not large by present standards, it represented a significant amount for poor men, both Black and White. Poor Whites continued to vote as the fee was waived or candidates paid the poll tax for their constituents. In addition, county officials frequently denied that payment had been made when Black voters appeared at the polling place as happened in Ocoee in 1920. Poll taxes could also be cumulative. That is, voters who skipped several elections and did not pay the poll tax or vote would be assessed the full payment for all the missed years when they decided to register and vote in a particular election. Florida rescinded the poll tax in 1938 as a result of scandals in which candidates paid the poll taxes of potential voters in order to assure a large turnout in favor of their election to office. In 1964, the 24th Amendment prohibiting the collection of a poll tax was ratified and added to the U.S. Constitution.

Unlike other taxes, such as property tax, the county did not instigate efforts to collect a poll tax. There was however a penalty that was born primarily by the Black community: poll taxes funded public schools. Legislators justified the underfunding of Black schools by noting that Blacks did not pay taxes in the same proportion as Whites. Even after paying the poll tax, Black citizens were often denied the ballot. Failure to pay the poll tax ensured disfranchisement and was used by legislators to justify lower funding for Black schools.

Literacy Tests

Literacy tests were based on the claims that voters should be literate in order to understand the issues and the positions of candidates. Since Black schools were so poorly funded and Black children worked alongside their parents in the fields, literacy tests targeted Black voters for exclusion from the exercise of the franchise. Failure enforced notions of Black unintelligibility perpetuated by White supremacy. These tests frequently required would-be voters to read and interpret passages from the U.S. Constitution or the appropriate state constitution. Since local officials chose the passage and determined whether the reader understood the text, Blacks could not pass the literacy test.

Florida did not have a literacy test but as Alexander Ackerman’s letter indicated in the previous exhibit, literacy was on trial in the way in which the ballot was organized. Random listing of names without indications of party or office meant that voters had to know the names of the preferred candidates and be able to identify them and mark the ballot in a limited period of time. Voters could receive no assistance in marking their ballots.

Multiple Ballot Boxes

States adopted a system of voting that required multiple ballot boxes for city, county, state, and federal elections with separate boxes for Democrats and Republicans. The purpose was not only to confuse poorly educated voters, but to limit federal election investigations to one or two ballot boxes.

Democratic Party White Primary

Probably the most effective mechanism for disfranchisement was the White Primary. The introduction of primary elections for selecting party candidates in the early 20th century was viewed as a positive election reform nationally. The primary removed the selection process from the backroom power brokers and placed the selection in the hands of party voters. In the Solid Democratic South, with a weak Republican Party, the White electorate chose candidates for state office in the primary to run in the general election. The Democratic winners of the primary contest enjoyed majority margins in the general election; consequently, the Democratic Party White Primary was, effectively, the only election that mattered. Democratic Party prohibition of Black voters from party membership disfranchised the Black electorate.

Challenges to White primaries came before the U.S. Supreme Court several times. In 1921 the court upheld the practice in Newbury v. United States; in 1927 the courts struck down the Texas primary law in Nixon v. Herndon.

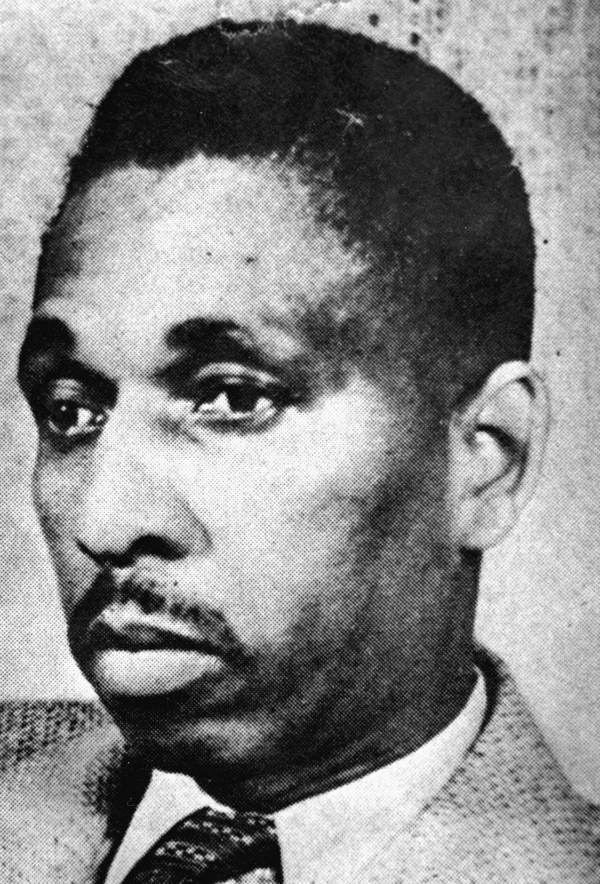

With the assistance of the NAACP, Lonnie E. Smith of Houston in Harris County sued election judge, S.S. Allwright. The Supreme Court outlawed the Democratic Party White Primary in Smith v. Allwright (1944). The landmark decision did not preclude other attempts to disfranchise Black voters but banned the White primary in Texas and the nation. A decade before the Brown decision, the ruling precipitated Black voter registration drives throughout the South including Florida.

The following year the Florida Supreme Court declared the state primary law unconstitutional. The abolition of the White primary quickly produced positive results for Florida’s Black voters. In 1940 only 3-6% of potential Black voters were registered to vote; in 1947 the numbers rose to 13-16% of Black voters. The statewide efforts of Harry Tyson Moore to register Black voters led to his death and that of his wife, Harriette Vyda Simms Moore, on Christmas evening 1951 when a bomb was detonated under their home in Mims, Florida.

(Harry T. Moore and the Moore Family Home images courtesy of Florida Memory. Harriette Moore image is public domain.)

Felony Conviction

The opening paragraph of the 1890 Mississippi Constitution provided the foundation for denying the ballot to convicted felons of specific crimes. The crimes listed are those that were believed to be common criminal acts by Blacks. Note that murder was not among the felonies for which a man could be disfranchised.

Mississippi Constitution, 1890

Article 12, Sec. 241. Every male inhabitant of this State, except idiots, insane persons and Indians not taxed, who is a citizen of the United States, twenty-one years old and upwards, who has resided in this State two years, and one year in the election district, or in the incorporated city or town, in which he offers to vote, and who is duly registered as provided in this article, and who has never been convicted of bribery, burglary, theft, arson, obtaining money or goods under false pretenses, perjury, forgery, embezzlement or bigamy, and who has paid, on or before the first day of February of the year in which he shall offer to vote, all taxes which may have been legally required of him, and which he has had an opportunity of paying according to law, for the two preceding years, and who shall produce to the officers holding the election satisfactory evidence that he has paid said taxes, is declared to be a qualified elector; but any minister of the gospel in charge of an organized church shall be entitled to vote after six months residence in the election district, if otherwise qualified.

Restoration of voting rights for convicted felons required a two-thirds vote by both houses of the legislature.

Road-building by a Florida chain gang in 1925.

(Photo courtesy of Florida Memory.)

Felony convictions disfranchised voters in Florida as well. In 2018 nearly 65 percent of the Florida electorate voted to amend the state constitution and restore voting rights to felons who had completed their sentences, including probation. Those convicted of murder or felony sexual offenses were excluded. Court challenges have delayed full restoration. In 2019 Governor Ron DeSantis approved Senate Bill 7066 that required felons to pay all fees and fines related to their cases before their voting rights could be restored. The law was challenged in court by attorneys with the Brennan Center, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), the Florida ACLU, and the NAACP Legal Defense Council and Education Fund, and initially won in both federal district court and the court of appeals. Judge Robert Hinkle concluded that the “pay-to-play” law amounted to an unconstitutional tax on voting.

However, the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals stopped the order from going into effect two months later. The Supreme Court refused to lift the 11th Circuit Court’s temporary order blocking felons from registering or voting a month before the state primary. In July 2021 opening statements from Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) attorneys were heard in a case against Governor DeSantis, charging that the bill denies people with felonies “the right to vote based purely on their low-income economic status.” While the 11th Court held there were no violations in the law of the 14th Amendment nor did the law constitute a poll tax barred under the 24th Amendment, the SPLC argued on behalf of two Black women with felony records, asserting the law not only violated the equal protection clause under the 14th Amendment, but under the 19th Amendment as well, which allowed women the right to vote.

(A collection of the primary court documents can be found at the bottom of the Brennan Center for Justice’s page.)

Conclusion

The suppression of the Black vote was multi-faceted and ongoing. For 80 years, from the first imposition of the poll tax by Florida in 1885 to the passage of the federal Voting Rights Act in 1965, Southern Black citizens had no representation in the making of political, social, and economic decisions. White political leaders enforced disfranchisement laws even though these restrictions on access to the vote also limited the voting rights of poor Whites and women (after 1920). Anti-Black violence remained a strategy for enforcing disfranchisement for which no one was held responsible.

Carter, Dan T. From George Wallace to Newt Gingrich: Race in the Conservative Counterculture, 1963-1994. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1996.

Cocelski, David S. and Timothy B. Tyson, eds. Democracy Betrayed: The Wilmington Race Riot and Its Legacy. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

“Federal Court Rules Florida Law That Undermined Voting Rights Restoration is Unconstitutional.” ACLU, May 24, 2020. https://www.aclu.org/press-releases/federal-court-rules-florida-law-undermined-voting-rights-restoration-unconstitutional.

Gilmore, Glenda Elizabeth. Gender & Jim Crow: Women and the Politics of White Supremacy in North Carolina, 1896. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

Green, Ben, Before His Time: The Untold Story of Harry T. Moore,America’s First Civil Rights Martyr. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1999.

Key, V. O. Southern Politics in State and Nation. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1949.

Kousser, J. Morgan. The Shaping of Southern Politics: Suffrage Restriction and the Establishment of the One-Party South, 1880-1910. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1974.

Lassiter, Matthew D. The Silent Majority: Suburban Politics in the Sunbelt South. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006.

“Litigation to Protect Amendment 4 in Florida.” Brennan Center for Justice, September 11, 2020. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/court-cases/litigation-protect-amendment-4-florida.

Mezzei, Patricia. “Ex-Felons in Florida Must Pay Fines Before Voting, Appeals Court Rules.” New York Times, September 11, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/11/us/florida-felon-voting-rights.html.

Nast, Thomas. “One Vote Less.” Presidential Campaigns: A Cartoon History, 1789-1976, accessed September 28, 2021, http://collections.libraries.indiana.edu/presidentialcartoons/items/show/133.

Perman, Michael. Struggle for Mastery: Disfranchisement in the South, 1888-1908. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

Raymond, Jonathan. “Arguments in suit over Florida ‘poll tax’ law to be heard at 11th Circuit in Atlanta today.” 11 Alive, July 22, 2021. https://www.11alive.com/article/news/politics/mccoy-v-desantis-florida-poll-tax-lawsuit-11th-circuit-atlanta/85-7344cc2c-e15f-4afd-b7a4-66e671caee98.

Road-building by a chain gang. 1925. State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory. <https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/29041>, accessed 21 September 2021.

“Wilmington, N.C. race riot, 1898.” The Daily Record. November 26, 1898. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Wilkerson-Freeman, Sarah. “The Second Battle for Woman Suffrage: Alabama White Women, the Poll Tax, and V. O. Key’s Master Narrative of Southern Politics.” Journal of Southern History 68, no. 2 (May 2002): 333-374.

Woodward, C. Vann. Origins of the New South, 1877-1913. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University, 1951, 1987.

Zucchino, David. Wilmington’s Lie: The Murderous Coup of 1898 and the Rise of White Supremacy. New York: Grove Press, 2021.