Chapter 4: Religious and Fraternal Organizations

Like other rural Black communities, Ocoee was not isolated from the national dialogue on race, equality, and the vote. Although Black citizens faced enormous barriers to voting and political engagement, they protested the violations and prohibitions of their citizenship and they provided social and charitable relief through religious and secular organizations. Churches, mutual benefit societies, and women’s groups were at the heart of the Black community. The overlap of Black fraternal, religious, and humanitarian organizations with groups such as the NAACP meant that even if a community did not have a lodge, branch, or club for all national organizations, they had access to, knowledge of, and participation in initiatives and efforts for political, social, and economic equality.

Prince Hall Masonic Lodge

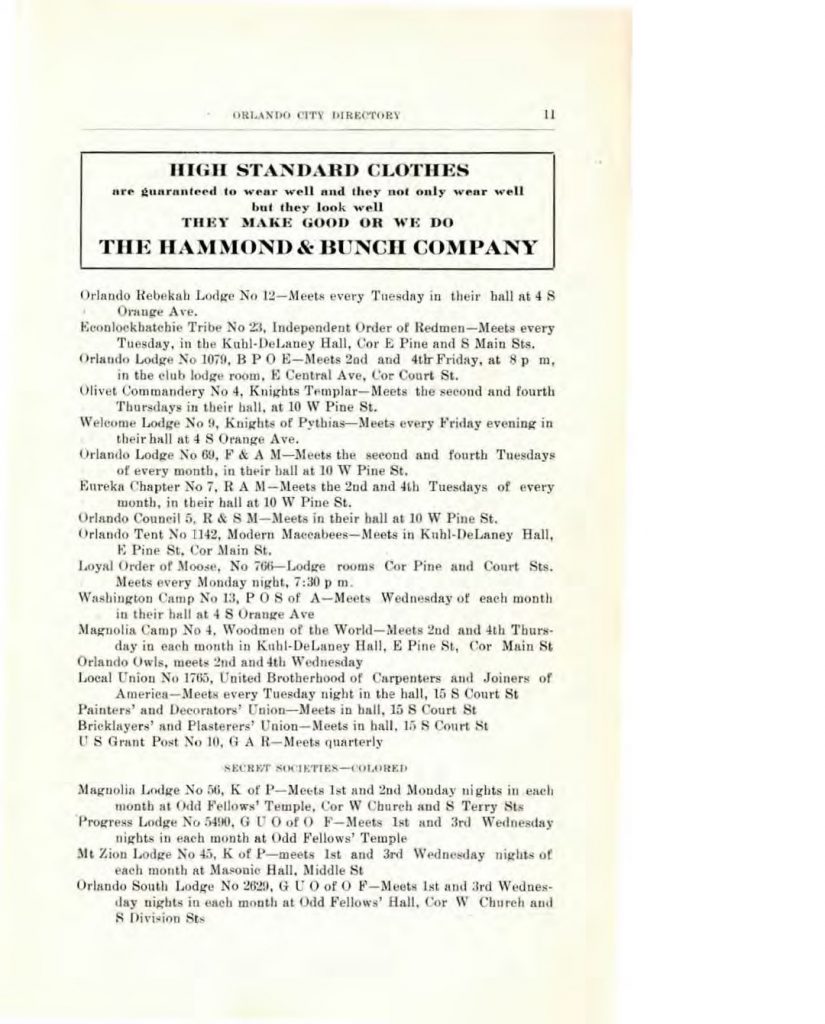

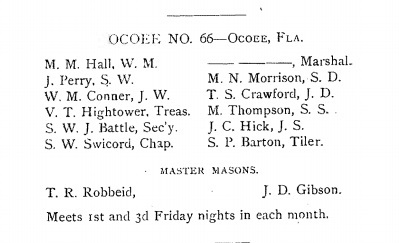

Prince Hall Masons of Ocoee Lodge, No. 66. July Perry is listed as Senior Warden and Valentine Hightower as Treasurer.

Many community leaders were members of the Prince Hall Masons, the Knights of Pythias and other fraternal organizations who played an integral role in challenging oppression. Grand Master David Daniel Powell of the Brothers of the Most Worshipful Union Grand Lodge of Florida set forth an initiative to encourage his fellow Prince Hall Masons to register voters for the 1920 Presidential Election. Ocoee Lodge #66 was burned to the ground during the Ocoee Massacre.

Knights of Pythias

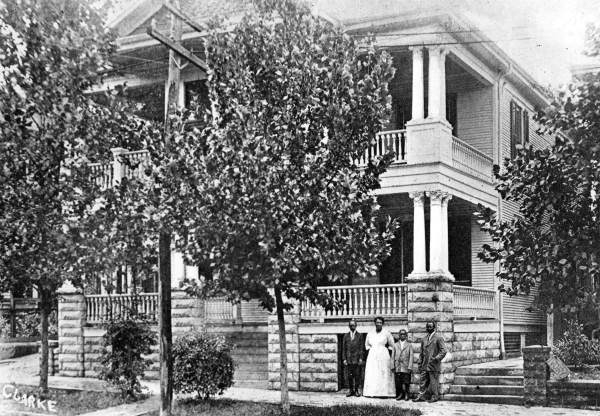

Knights of Pythias lodge and the home of W.W. Andrews – Jacksonville, Florida. c.1919. (Courtesy of Florida Memory.)

The Colored Knights of Pythias played a pivotal role in registering Black members across the state of Florida to vote. A national fraternal organization founded in the 1880s after Black men were denied membership in the White brotherhood of the same name, by the early twentieth century the Pythians boasted the highest rates of membership of Black individuals of any fraternal order in Florida. The Pythians operated under the three core tenets of friendship, charity, and benevolence that inspired the organization’s activism.

National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (1896-1914), National Association of Colored Women (1914-present)

Meeting of the Southeastern Branch of the National Association of Colored Women. (Photo courtesy of RICHES.)

Founded in 1896 in Washington, D.C., the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs organized around the principles that included protection for women and children, education, racial harmony, and woman suffrage. Their motto, “Lifting as We Climb,” indicated that while they fought for the rights of women, they believed that all Blacks should enjoy the benefits of equality and full citizenship. The first president of NACWC was Mary Church Terrell whose diplomatic and organizational skills enabled the organization to climb to 100,000 members by 1924. Members in the early years of the NACWC came from the Black elite, but by 1920 middle and working class Black women joined as well.

Mary McLeod Bethune was a member of the NACW and served as president of the organization from 1924 to 1928. She was also president of the Florida Branch of NACW. Once women won suffrage in 1920 she bicycled from door to door in Daytona urging Blacks to “eat your bread without butter, but pay your poll tax!” On election day, Bethune marched at the head of Blacks going to the polls, having advised that they should go together to minimize the threat of violence.

In Orange County, there were chapters of NACW in Orlando (Parramore) and Eatonville.

Colored women’s clubs, their presidents, and locations in Central Florida in the early twentieth century

- Woman Development Club – Mrs. A. Detwyller – Orlando

- Harriet Tubman Mothers’ Club – Mrs. Anna E. Hudson – Tampa

- Amanda Smith Club – Mrs. Lucy Moore – Daytona

- Jennie Dean Club – Mrs. Flora Brooks – Daytona

- Sojourner Truth – Mrs. S.B. Alexander – Ocala

- Colored Women Federated Club – Mrs. F. Hughes – St. Petersburg

- Child’s Conservative League – Mrs. Josie L. James – Daytona

- Civic Improvement Club – Miss N.H. Gantling – Daytona

- Emma Freeman Club – Mrs. Martha R. Williams – Port Orange

- Daytona Normal and Industrial Institute Club – Miss Irene V. Roberts – Daytona

- Ever Green – Mrs. P.E. Bacon – Daytona

- Hungerford Normal and Industrial School – Mrs. E.B. Baker – Maitland

- Eastern Star Community Club – Mrs. I.J. Alston – Tampa

- Needle Craft Club – Mrs. E.V. Patterson – Tampa

Other Colored women’s clubs, their presidents, and locations in Florida in the early twentieth century

- Old Folks Home – Miss Eartha M.M. White – Jacksonville

- West End Fidelity – Mrs. S.F. King – Jacksonville

- Excelsior Reading Circle – Mrs. Louise A. Sullivan – Gainesville

- Florida F. and M.C. Women’s Club – Mrs. C.H. Martin – Tallahassee

- Dorcas – Mrs. M.L. Trapp – Palatka

- Excelsior – Mrs. M.M. Drakford – Palatka

- Woman’s Literary Art and Social Club – Mrs. J.A. Manker – Live Oak

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)

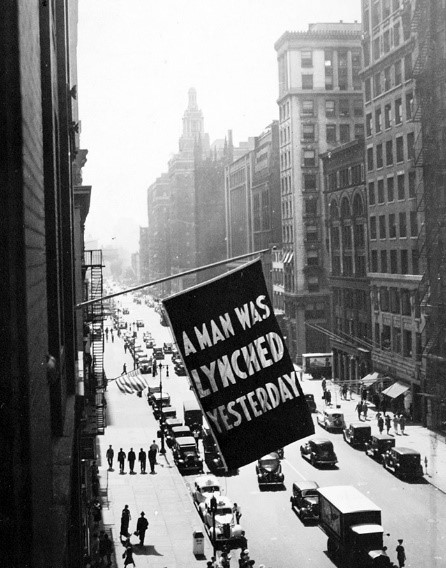

A flag flown from an upper story window of the NAACP headquarters on 69 Fifth Avenue, New York City, announcing that “a man was lynched yesterday.” (Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.)

The NAACP was founded in 1909 and is the oldest and largest civil rights organization in the United States. By 1920, the NAACP had 100,000 members in 40 states and the District of Columbia and 353 branches. The NAACP defended Blacks in court against inequities in the law. NAACP lawyers tested the constitutionality of the law, most notably in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka in 1954. As part of their work they investigated and documented lynchings in the United States. This work would bring Walter White, assistant field agent, to Orange County in November 1920. W.E.B. DuBois edited the NAACP’s monthly journal, The Crisis.

In 1920 the NAACP called on Black fraternal organizations to sponsor campaigns that would encourage their members to register, pay the poll tax, and vote.

Religious Life

The churches in Ocoee anchored the community, with the two neighborhoods identified as Methodist and Baptist. Churches supported faith, encouraged hope, provided charity, gave song to dreams, and provided a forum for social justice. Black ministers were often the bridge between congregations and the white community. Church structures became the first schools in Black communities before either the Julius Rosenwald Foundation or county and municipal governments built schoolhouses for Black children. Black Ocoee supported two churches, an African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church and Friendship Missionary Baptist Church.

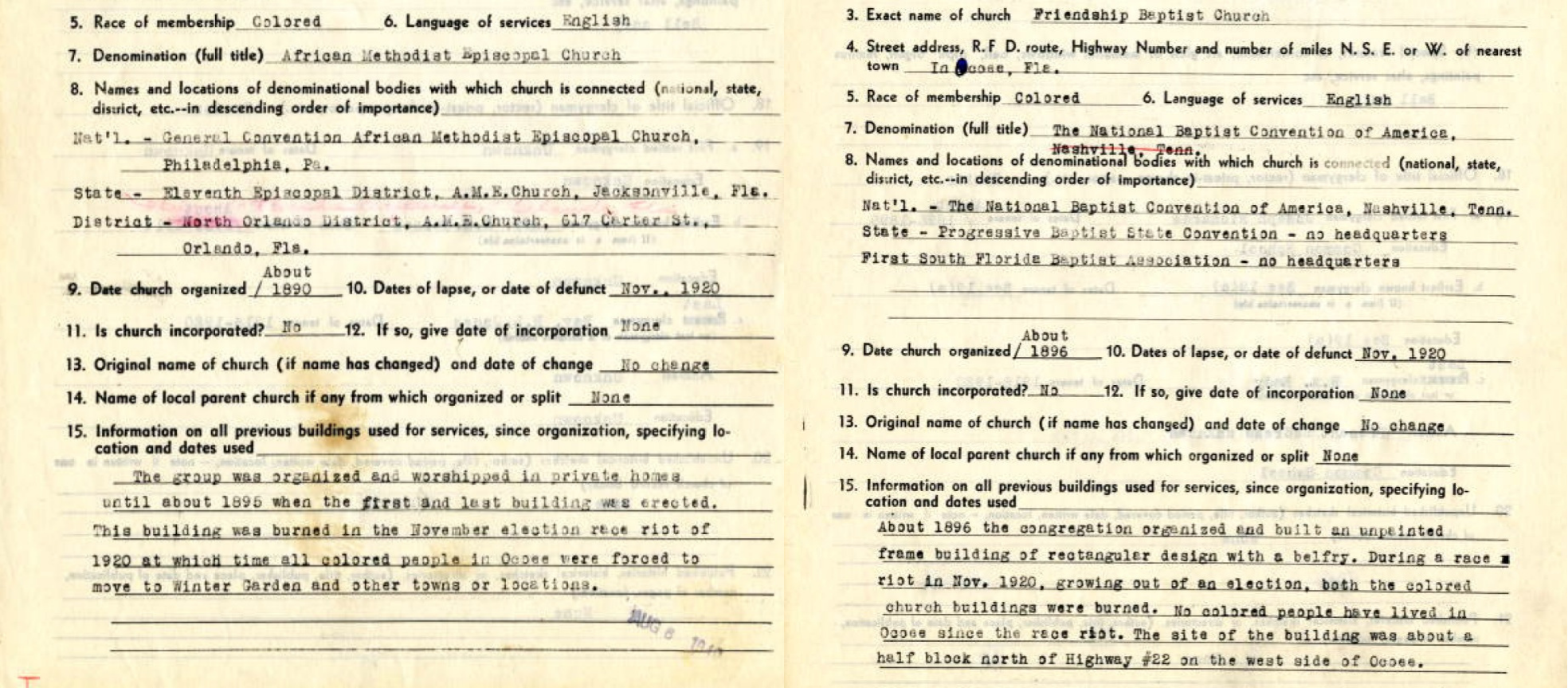

WPA church records for African Methodist Episcopal Church and Friendship Baptist Church. (Image courtesy of Florida Memory.)

The AME denomination has its origins in Philadelphia. In 1794, Richard Allan a former slave, became the first pastor of Bethel AME and in 1816 a court decision empowered Blacks to establish a separate institution, the AME Church. During the Civil War, missionaries from northern states came South to establish churches among the freedmen.

Black Missionary Baptist Churches follow familiar Baptist beliefs in local congregational autonomy, salvation by faith, adult baptism and membership, and the authority of the scripture. The Black Missionary Church emerged in the 1880s, when former slaves who had been reared in the Baptist traditions established the Foreign Mission Baptist Convention, the American Baptist Convention in 1886, and the Baptist National Education Convention in 1893. The three organizations united to form the National Baptist Convention in 1895. Early in the 20th century the Convention split into the National Baptist Convention of America and the National Baptist Convention USA.

Black Citizenship and WWI

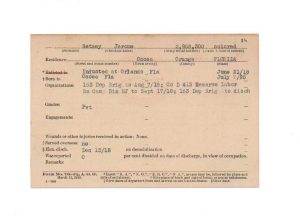

WWI Service Card for Jerome Betsey of Ocoee. (Image courtesy of Florida Memory.) For more examples of service cards from Black residents of Ocoee see Florida Memory by clicking here.

When the United States joined World War I in 1917, the federal government instituted a draft for all eligible men between the ages of 21 and 31, including Black men. Lafayette Hamiter registered on the day of the first draft on June 5, 1917, and later enlisted on November 28, 1917. He was assigned to Company C of the 312th Labor/Service Battalion of the Quartermaster Corps (QMC). Like many other Black men who enlisted or were selected for military service, Lafayette Hamiter was placed with a battalion that experienced little combat training to appease Southern White supremacy fears of weapons in Black hands.

The Florida Metropolis (Jacksonville, FL). “Grand Chancellor Andrews’ Official Visits.” April 1, 1920, 15. Provided by the George A. Smathers Libraries, University of Florida.

Green, S.W., Joseph L. Jones, and E.A. Williams. History and Manual of the Colored Knights of Pythias. Nashville: National Baptist Publishing Board, 1917.

The Ocala Evening Star. “Colored K. of P. Convention.” May 18, 1920, 4. Accessed October 29, 2020. Newspapers.com.

Orlando Evening Star. “Negro Pythians Bring Convention to Close.” May 24, 1918, 1. Accessed October 29, 2020. Newspapers.com.

Ortiz, Paul. Emancipation Betrayed: The Hidden History of Black Organizing and White Violence in Florida from Reconstruction to the Bloody Election of 1920. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

Tallahassee Democrat. “K.P. Convention Here Next Week.” May 14, 1915, 1. Accessed October 29, 2020. Newspapers.com.

The Tampa Times. “Negro K. of P. Meeting Here.” May 20, 1919, 8. Accessed October 29, 2020. Newspapers.com.