Chapter 12: Ocoee 100 Years Later

A visitor passing through Ocoee today might never realize that the bloodiest election-day violence in American history took place in that town a century ago. Now stretching along West Colonial Drive, Ocoee seems like any other suburban community in the South, with mile after mile of commercial and low-rise office space, subdivisions of similar houses, and new schools and hospitals. To find remnants of the town that existed in 1920, you must exit the six-lane road onto Bluford Ave, a two-lane street named for the town’s original landholder, Bluford Sims. A number of landmarks have been replaced with modern structures including a new city hall complex on the shores of Starke Lake. No signage indicates the areas that were the Northern and Southern Quarters, the homes of Blacks living in Ocoee before November 1920. A few stores and older homes, and an American Gothic church are reminders of the town’s past. One is struck by the small size of the old town. The geographic space between Black and White meant that no one was anonymous. They knew one another well, even across the social and political gulf of white supremacy that separated them absolutely, granting power to Whites to inflict violence on Black citizens.

Past and Future in Ocoee

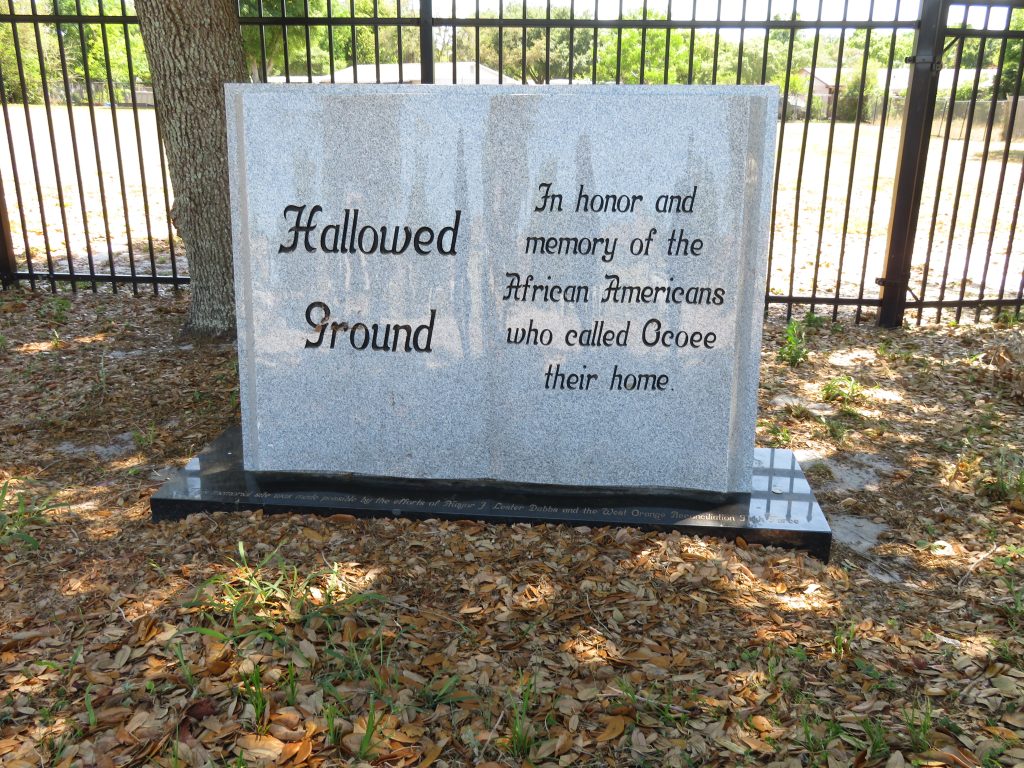

The efforts of old Ocoee to suppress knowledge about and discussions of the massacre focused primarily on the exclusion of Black presence in the town: with no Black presence, there was nothing to discuss. Yet even in the sundown town era, the history reasserted itself periodically in public references to voting rights within Orange County and in student papers written by Ocoee residents Vernon E. Parrish at the University of Florida (1949) and Lester Dabbs at Stetson University (1969). In the 1980s, more than 15 years after the passage of the federal Civil Rights Act, Black families began moving into Ocoee again.

Today, (2020), the 47,000+ people living in Ocoee and the surrounding subdivisions include a diverse population of Black (19.9%), white non-Hispanic (43.3%), Hispanic (28.0%), and Asian (5.5%) families. Their voting influence has placed two Black members, Larry Brinson Sr., and George Oliver III, on the four-member city commission.

Ocoee City Commission. (Left to right, Larry Brinson, Sr., Rosemary Wilsen, Rusty Johnson, Richard Firstner, George Oliver III.)

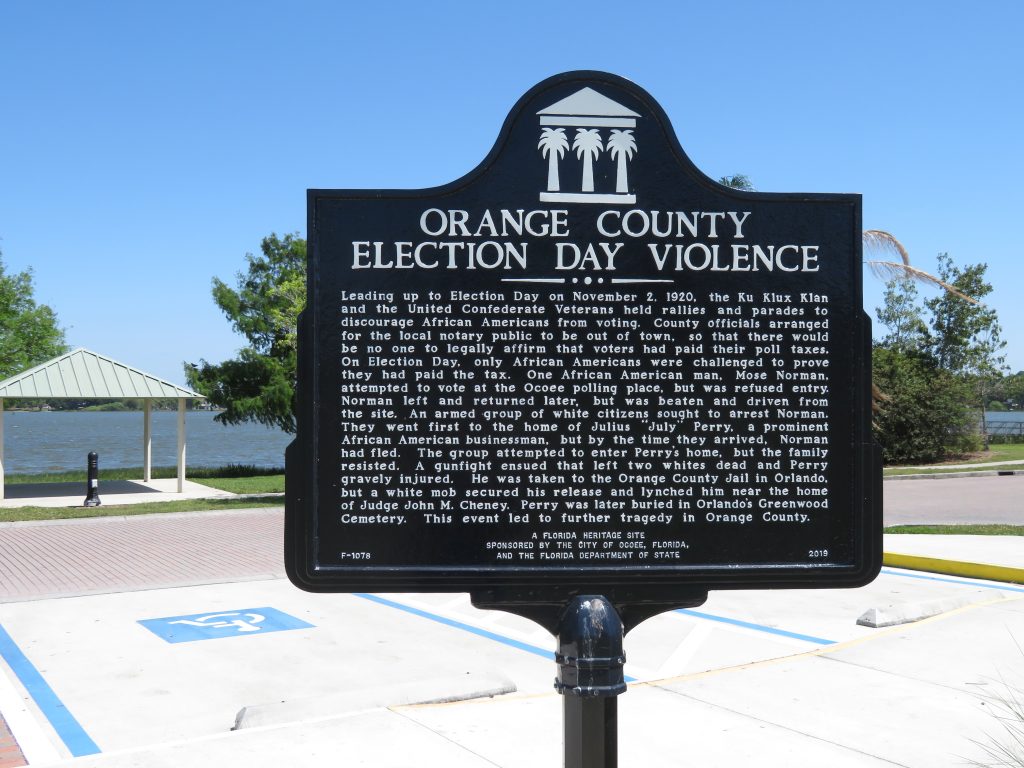

The city created a Human Relations Diversity Board consisting of 7-13 voting members who reside and own real property or businesses in Ocoee. The goal of the board is “to promote understanding, respect, goodwill, and equality.” In 2018, the City of Ocoee issued a Proclamation acknowledging the massacre and the town’s role in the events. In November 2020, the city held a four-day “100 Year Remembrance Ceremony Event” that included a day to focus on each of the following: The Ocoee Story, Honoring the Memory, Healing the Wound, and Unveiling the Historic Marker. Each of these milestones represent a step forward out of the violent past. With each step forward comes recognition that there is still much to be done.

Sign directing visitors to the historical marker. (Photo courtesy of Amy Giroux, UCF.)

U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Ocoee city, Florida