Chapter 2: The Ocoee Massacre in National Context

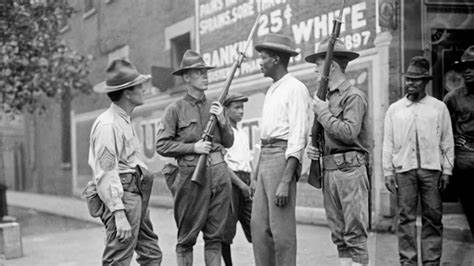

The Ocoee Massacre was not a random event, but part of a pattern of intimidation and violence that marked the post-Civil War South generally and the years 1915-1920 specifically. White southerners had devoted decades of work to construct state constitutions and enact laws that disfranchised Black voters and denied Black citizens equal access to public spaces. When law failed to accomplish White supremacy, violence in the form of arson, beatings, and lynchings occurred. Florida was a particularly brutal place for Blacks. Over the period 1880-1950, relative to its population size, Florida had more lynchings than any other state. Six Florida counties were listed among the 25 most violent counties in the South, including Orange County. In the post-WWI era, anti-Black violence became a public spectacle that was often advertised in advance and attended by men, women, and children who posed for photographs with and collected souvenirs from the brutalized bodies.

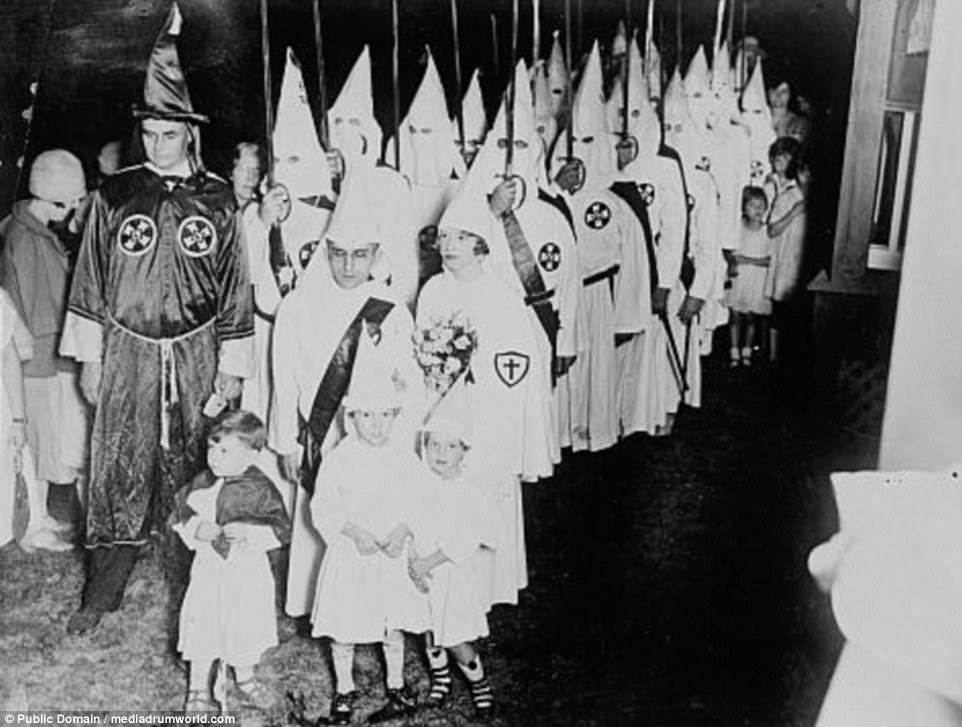

The Ku Klux Klan

The second manifestation of the KKK was more open and spread across the nation, claiming millions of members by 1925. The Klan claimed to protect American families and Protestant Christianity. It preached White supremacy, nativism, anti-Catholicism and anti-Semitism, and supported Prohibition.

The revival of the KKK in 1915 coincided with the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the Civil War and the release of D.W. Griffith’s, The Birth of a Nation. The silent film venerated the Lost Cause, lent credibility to the pseudo-legitimacy of the Dunning School of historiography, and justified anti-Black violence. Based on the Thomas Dixon novel, The Clansman, published in 1905, it was the first film screened at the White House during the first term of Woodrow Wilson. The film was a cultural and technological spectacle that reified American legal and customary apartheid. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) protested the film’s anti-Black representations.

World War I

The 1917 American entry into World War I produced a national propaganda campaign to “sell” the war to a nation that had re-elected Woodrow Wilson to his second term as president on the slogan “He kept us out of war.” Americans needed a purpose worth fighting for and Wilson gave it to them: “Make the World Safe for Democracy.” Whites everywhere and people of color in the United States and the colonized areas of the world heard very different things in that slogan. Convincing the American people to send their sons into a war that already had claimed millions of lives and to make the economic sacrifices necessary to fund the equipping of a modern military force also required an intense marshaling of nationalism that centered on naming and identifying with 100% Americanism. Rumors questioning the loyalty of German-American citizens, immigrants, and Blacks abounded, with violence against those identified as suspicious intensifying and increasing. The end of the war, however, did not return international peace and did not end the domestic violence, especially violence against Black American citizens.

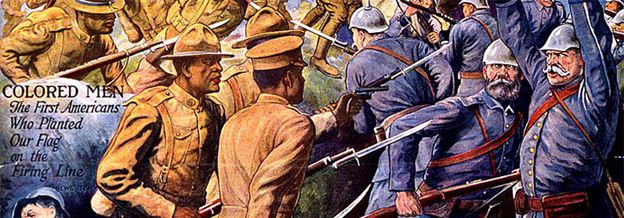

With a noble cause they saw as worthy of sacrifice, White soldiers and political leaders in the United States viewed the military experience of war as an opportunity to demonstrate heroism. Colonized people of color around the world believed that winning the war would enable them to rule themselves. Black citizens in the United States lent their support to the war with the expectation that service on behalf of the nation would entitle them to the full rights of citizenship, even though some Black leaders warned that fighting in all the wars over the preceding 150 years of the nation’s history had not produced the outcome they sought. Whites viewed Black military service as a means to acquire labor for support services for White soldiers fighting in the trenches. When the war ended colonized people pursued their claims to self-rule and Black soldiers returned to the United States to claim their rights; White soldiers returned home validated in their sense of White superiority.

The war deepened racial, cultural, and political divisions at home. The use of the draft to fill the military ranks illuminated racial and class divisions. More than any other geographic region, White southerners avoided registration and the draft. Labeling the conflict “a rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight,” men pleaded ignorance of the process and/or hid in the mountains and forests to avoid military service. Ministers to the pacifist Christian denominations serving congregations in the Appalachian Mountains counseled their members on mechanisms to avoid the draft. WWI Congressional Medal of Honor winner, Sgt. Alvin York of Tennessee, first considered avoiding the draft before entering the army and going to war.

Southern Whites expressed considerable concern over the prospect of Black men receiving military training. Worried that returning Black veterans would take up arms against their local oppressors, they acceded to the drafting of Black men only after certainty that Black draftees would be used in support services rather than as front-line soldiers. Despite those assurances, two divisions of Black soldiers saw service in the trenches of France: the 92nd and the 93rd Divisions. The men and officers of the 92nd Division, known as the “Buffalo Soldiers,” served in the Meuse-Argonne offensive from September to November 1918. The 93rd Division fought under French army command and included the “Harlem Hellfighters” and the “Black Devils.” That division fought in the Second Battle of the Marne among other engagements. The soldiers of the 93rd Division earned 2 Congressional Medals of Honor, 75 Distinguished Service Crosses, and 527 Croix de Guerre (France).

At home, White supporters of the war demanded extraordinary limits on personal and public behavior that supported a narrow definition of patriotism. Americans of German heritage were vilified and lost jobs, businesses, and homes. In Tampa, the German-American Club, a pillar of philanthropy in the city, was forced to sell its building. Ordinary individuals were pressured to make their patriotism evident through the purchase of Liberty Bonds. In March 1917, the American Protective League (APL), a private organization with semi-official approval, claimed 250,000 members in 600 cities, spied on Americans and reported their activities to the Bureau of Investigation (BOI), the forerunner of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). League members reported wartime food and gasoline violations, illegal production and sale of alcohol, those who spoke out against the war, draft evaders, socialists, union organizers, anarchists, pacifists, and, of course, Germans. Concern about the American Protective League reached all the way to the White House, but no action was taken to disband the organization until after the war. In 1919, U.S. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer labeled the materials collected by the APL as “gossip, hearsay information, conclusions, and inferences.” The work of the APL nevertheless contributed to a climate of distrust and fear that continued after the end of the war.

Soldiers returned to a United States and South roiled by turmoil: an influenza pandemic, an active Ku Klux Klan, a nation still bent on 100% Americanism now refocused on expelling Communists, and both old and new claims for full citizenship from women and Blacks. In 1919 a series of anti-Black riots from June to October, a period James Weldon Johnson labeled the “Red Summer,” demonstrated White determination to re-assert whatever authority they thought had been eroded during the course of the war.

The outbreak of the influenza pandemic in the waning days of WWI added to the fears and anxieties of Floridians and all Americans. As recent research shows, the mortality rates among Blacks were higher than those among Whites. Within steps of the grave of July Perry, who was lynched on November 3, 1920 are the graves of Orange County African Americans who all died in fall 1918, presumably the victims of the pandemic.

Red Summer of 1919

James Weldon Johnson, born in Jacksonville and Field Secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), labeled 1919 the “Red Summer” following an extraordinary 2½ month period that witnessed 21 anti-Black riots in towns and cities across the nation. In the course of the year, a report to the New York Times listed 60 riots. Despite a previous year of unrest, Blacks in Florida entered 1920 determined to put their right to vote to the test.

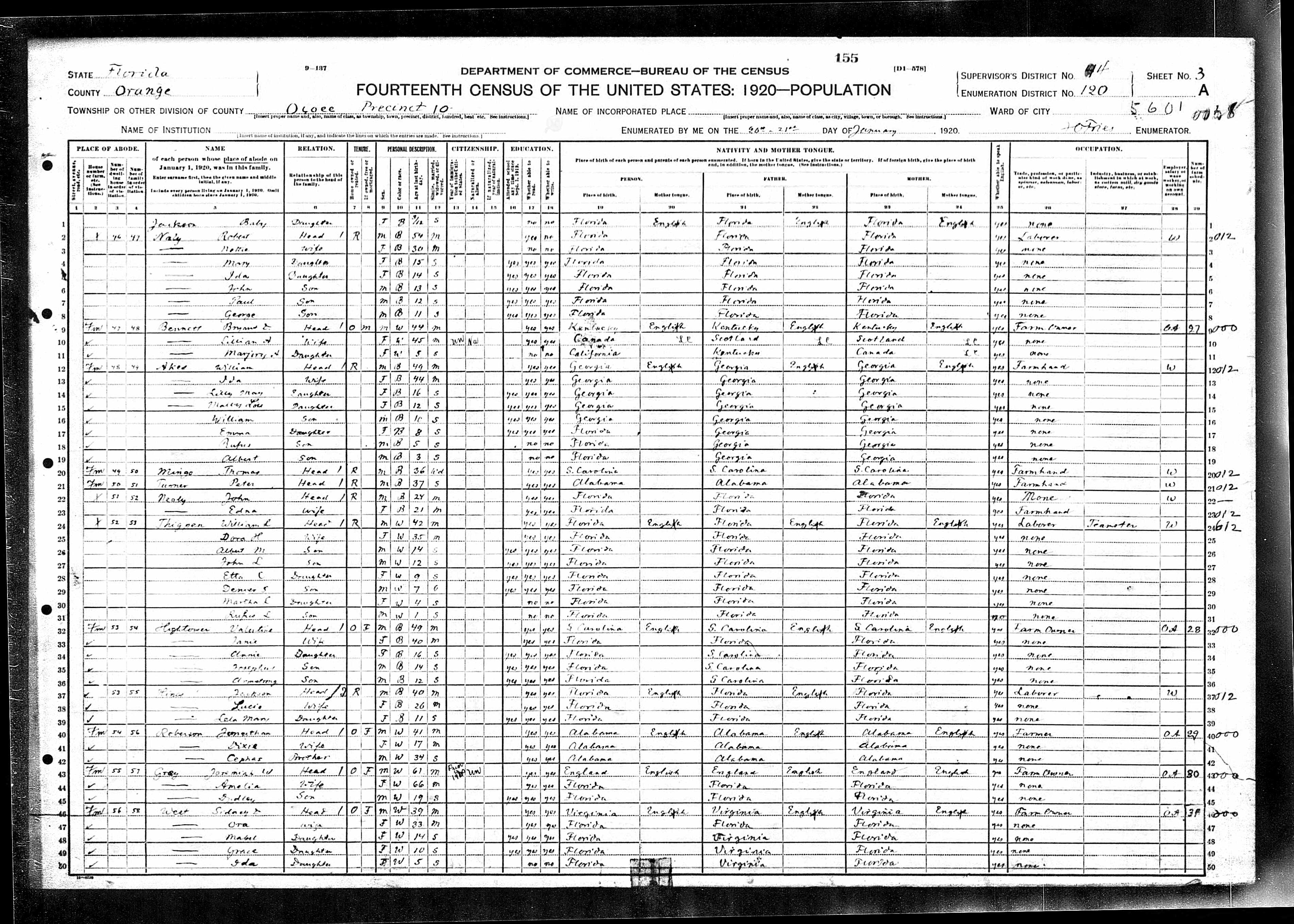

1920 Census

The 1920 Census coincided with the presidential election and offered the NAACP an opportunity to address Black voter disfranchisement before Congress. When the two events occur simultaneously, there is a record of population figures, registered voters, and ballots cast in an election in which the entire nation votes. The NAACP prepared to use that information to demonstrate to the U.S. House Committee on Apportionment that southern states systematically denied the right to vote to Black citizens. They would ask the committee to invoke Section 2 of the 14th Amendment, which enables Congress to reduce the number of representatives to the U.S. House if the state denies the vote to citizens entitled to the franchise. To improve their case, Black citizens were encouraged to register to vote.

Ratification of the 19th Amendment

The campaign to enfranchise women began with the 1848 conference at Seneca Falls, New York, that included Black and White women and men. Seventy-two years later, in August 1920, when all women in the United States won the right to vote, the politics within the woman suffrage movement was more complicated. Black women and White women fought hard for the right to cast their ballots in a democratic nation roiled by racism and nativism, and although they did so under a loose umbrella of the suffrage movement, they campaigned separately. When the push for a constitutional amendment gained traction in the first decade of the twentieth century, the suffrage advocates who were the inheritors of their Black and White abolitionist grandmothers abandoned Black women in hopes of gaining support for White woman suffrage in the South.

The Election of 1920

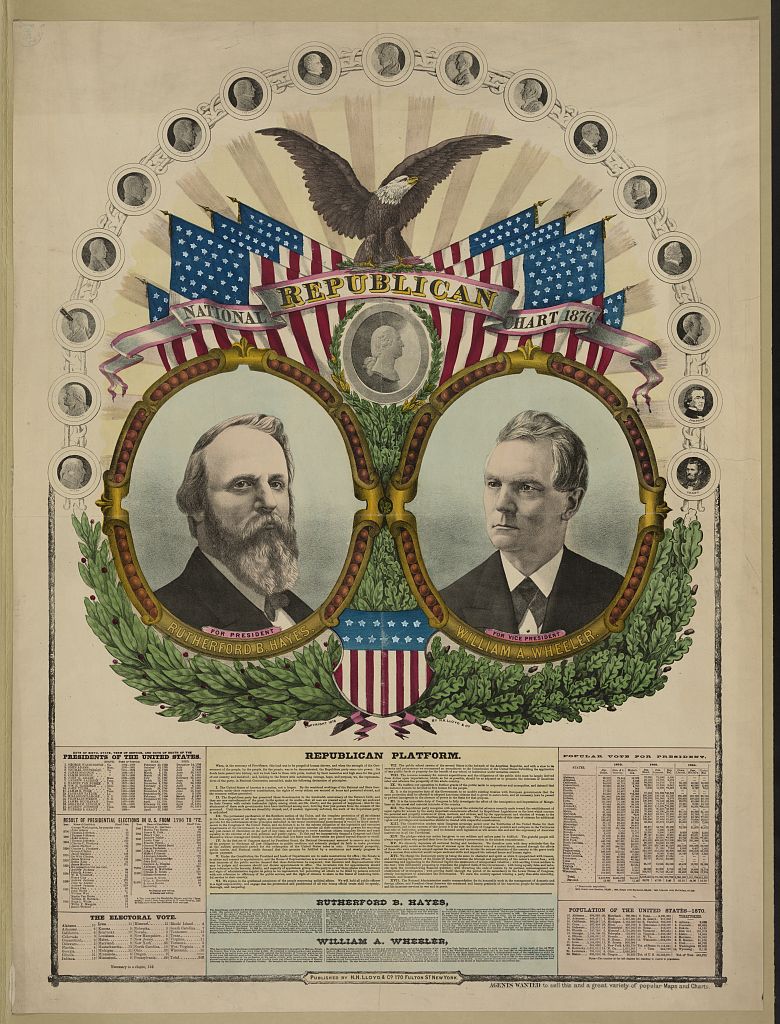

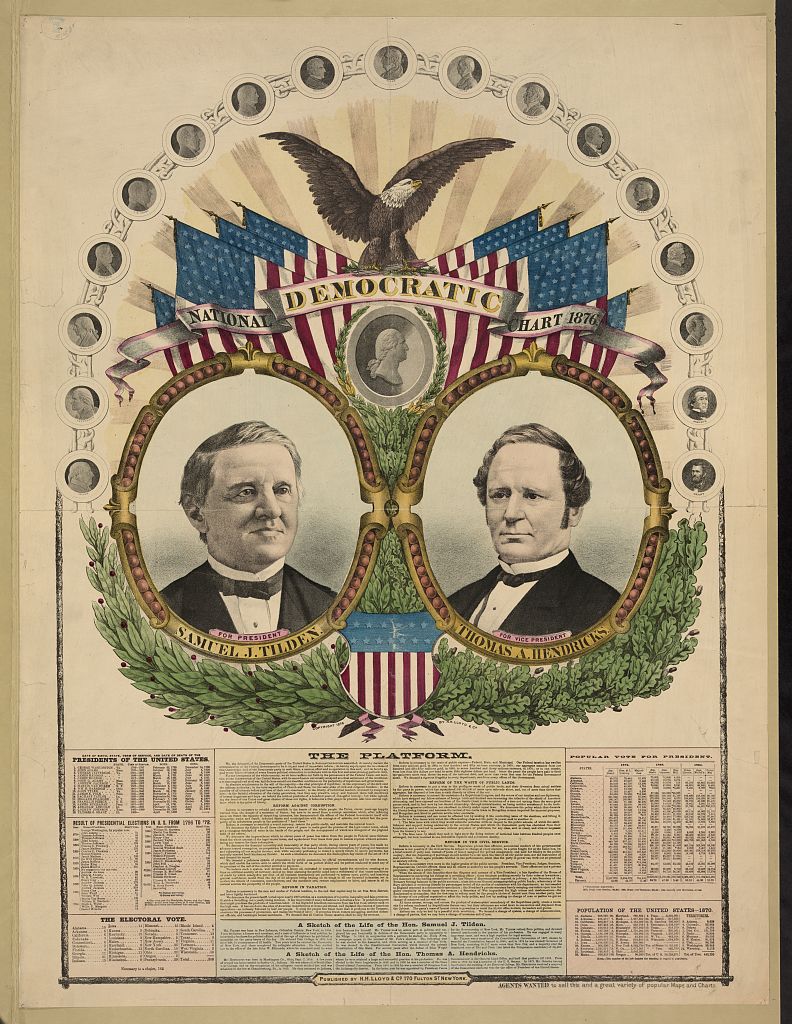

The election of 1920 was the first since the end of WWI and the first election in which all women voted. It took place in the midst of a recession and pitted Republicans Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge against Democrats James M. Cox and Franklin D. Roosevelt. Both Harding and Cox were political leaders in Ohio, a swing state. Harding was a U.S. Senator and Cox was Governor. At issue was the U.S. position in the world, namely whether the nation would join the League of Nations. Harding essentially ran against Woodrow Wilson, campaigning against progressive actions at home and internationally. He promised a “return to normalcy.” He easily defeated Cox with 60% of the vote, winning 37 states and 404 electoral votes. The Harding administration is remembered primarily for its corruption, especially the Teapot Dome scandal. Harding died on August 2, 1923, in San Francisco of a heart attack.

Florida voters also elected a U.S. Senator in 1920. Republican John M. Cheney (Orlando) ran against Democratic incumbent Duncan U. Fletcher (Jacksonville). Cheney lost with 26% of the vote to Fletcher’s 69.5%. Of Fletcher’s 4 successful Senate campaigns, the 1920 campaign was the most competitive. At the time of the election, Cheney was an attorney in Orlando; he represented Black clients and engaged in voter registration drives in the Black communities of Orange County. In 1912, William Howard Taft appointed Cheney to a vacant position on the federal bench of the U.S. District Court of Southern Florida and he served for several months. In March 1913, a Democratic Senate defeated his formal nomination.

Blight, David W., Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Jensen, Joan M., The Price of Vigilance. New York: Rand McNally & Company, 1968.

Keith, Jeanette, Rich Man’s War, Poor Man’s Fight: Race, Class, and Power in the Rural South during the First World War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Kornweibel Jr, Theodore, “Investigate Everything”: Federal Efforts to Compel Black Loyalty during World War I. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002.

Litwack, Leon F., “The Birth of a Nation” in Past Imperfect: History According to the Movies, ed. by Mark C. Carnes. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1995, 136-141.

Williams, Chad L., Torchbearers of Democracy: African American Soldiers in World War I Era. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.