Chapter 5: The Ocoee Massacre, November 2-3, 1920

Introduction

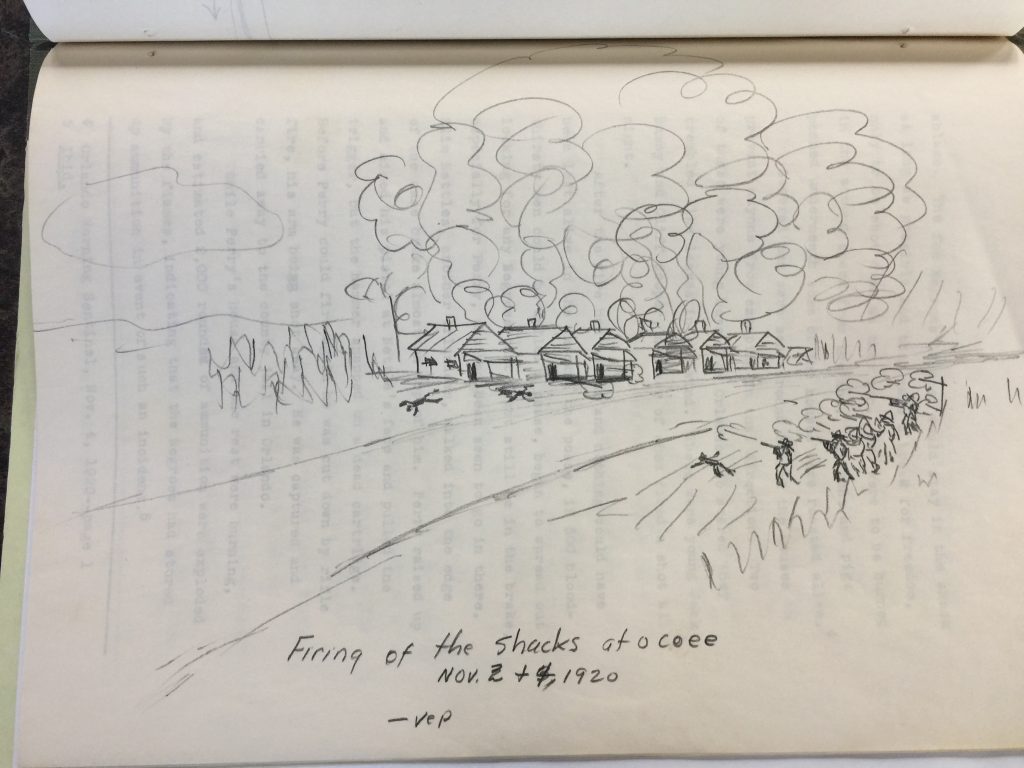

No photographs exist of the violence or the destroyed homes, school, churches and Masonic lodge. We must depend on word pictures to know what happened and most of the words have been provided by Whites who were complicit in the racial violence. Blacks fled for their lives on the night of November 2-3, 1920. When they arrived at a safe place, they feared violent retaliation and remained quiet. As is true of survivors of other traumatic events, there were those who never found the words to express what they saw and experienced. For many of Ocoee’s Black survivors a reckoning with the past came only when grandchildren and great-grandchildren asked questions about that night so long ago.

The Election Campaign Season: Who Will Vote?

The fall of 1920, like all election seasons that include a presidential campaign, was filled with rallies, marches, speeches, and political party efforts to get out the vote. But the 1920 election was more ominous as the NAACP with the support of Black fraternal organizations made it clear that southern voter disfranchising laws would be challenged by Black voters. The addition of women to the voting rolls in the last months of the campaign added to the sense that this could be a pivotal election.

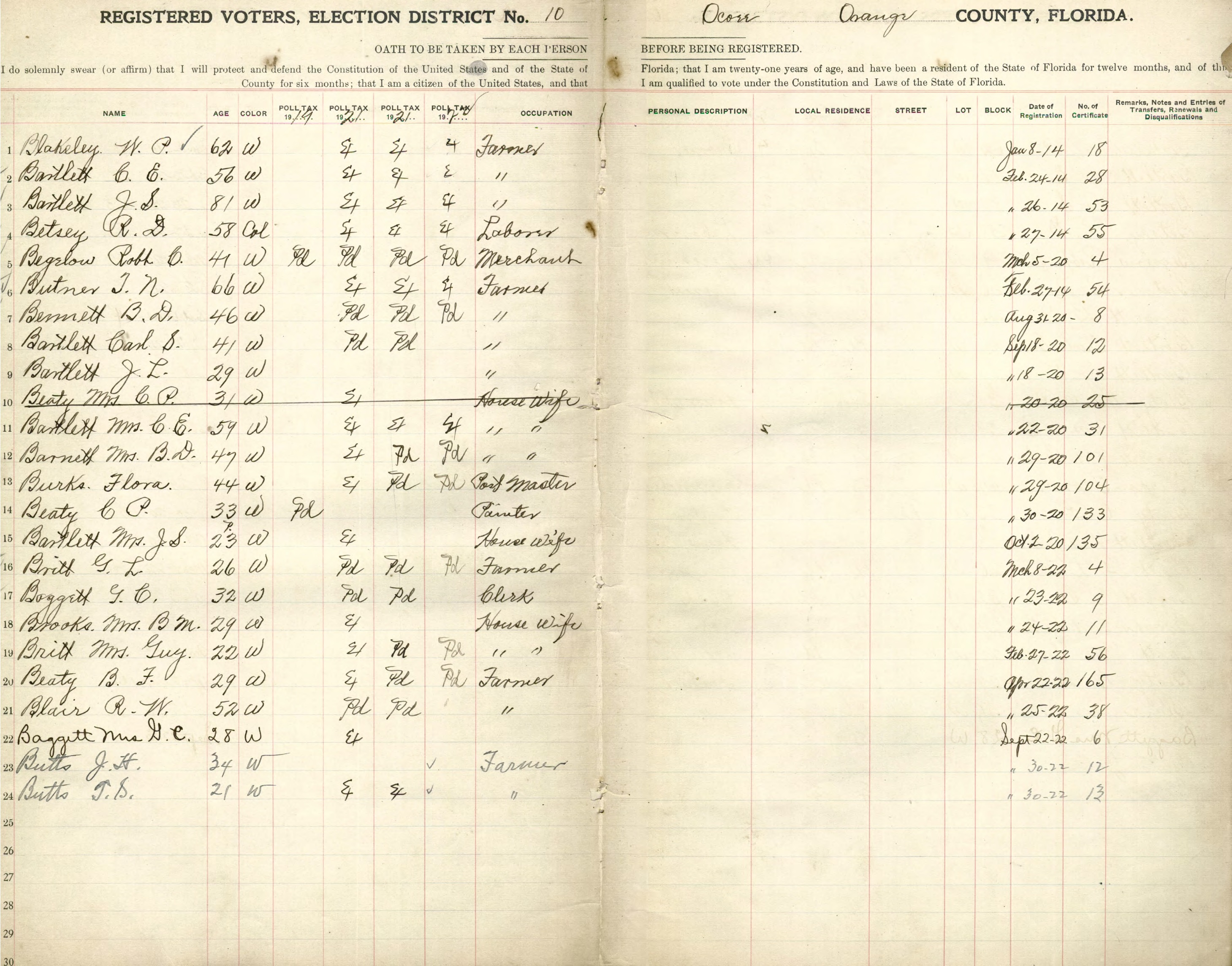

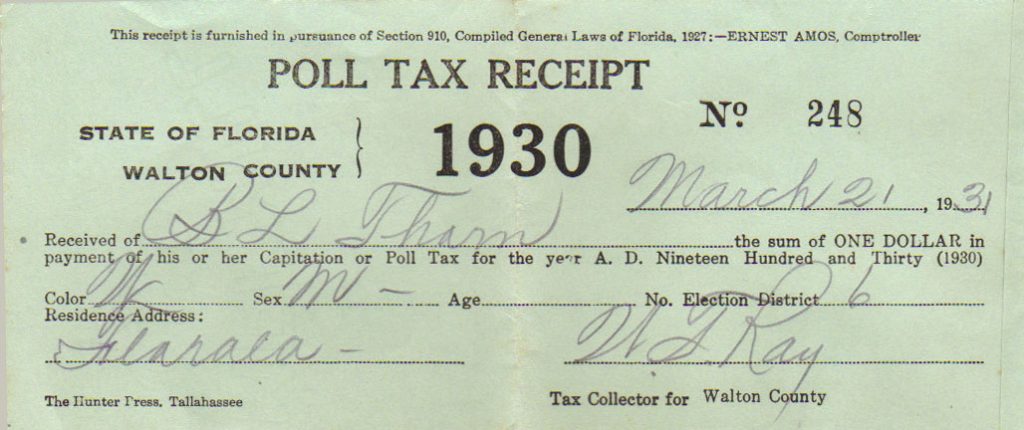

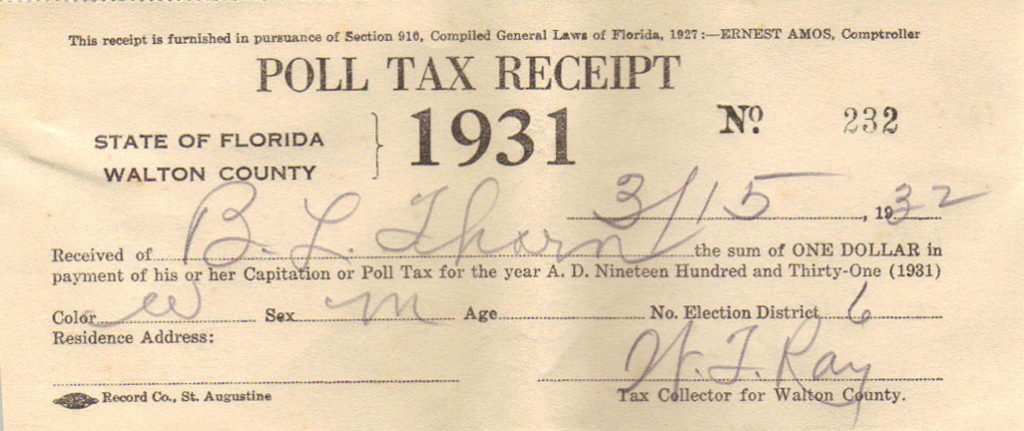

Florida laws required registration and the payment of a poll tax to cast a ballot.

Poll tax receipts from Walton County, Florida. (Images courtesy of Walton County Supervisor of Elections Office.)

”Eat your bread without butter but pay your poll tax!” -Mary McLeod Bethune

White Pressure to Prevent Black Voting in the 1920 Election

Across the state, Black voting activists met White resistance, with verbal warnings and violence. Reports from Live Oak in Suwanee County and Quincy in Gadsden County detailed the pressure exerted against registration of Black voters. In Orlando, John M. Cheney, local attorney and Republican candidate for the U.S. Senate, met with Black leaders and urged them to promote voter registration and payment of the poll tax. His actions and those of other White Republicans soon came to the attention of the Ku Klux Klan.

On October 30, Klansmen across the South marched. In some cities the parades included as many as 1000 marchers who carried banners through Black neighborhoods as a way to intimidate Black voters and discourage them from going to the polls on election day. Five hundred Klansmen marched in Orlando. In Daytona, the KKK visited Mary McLeod Bethune’s school for girls; on election day, she marched with a contingent of Black voters to the polls in a show of strength. Jacksonville held the largest Klan parade, a reported 1000 participants.

Election Day, 1920

The following sequence of events have been pieced together from a variety of newspapers, investigations, and academic studies. Conflicting reports are noted in parentheses.

Political cartoon depicting a black woman being distanced from a white suffragist. Both carry signs that read “Votes for women.” Caption reads, “Votes for WHITE women.” (Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.)

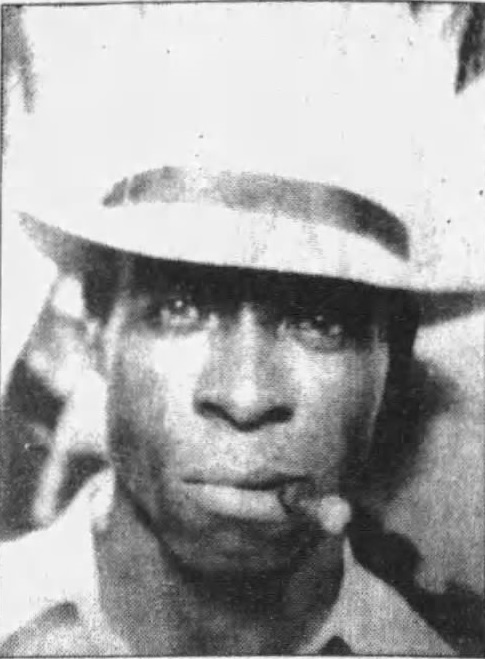

November 2, 1920 saw Floridians, men and women, heading to the polls. Many Black Floridians cast their ballots, but there were reports of violence across the state. In Jacksonville, NAACP Field Investigator Walter White reported that more than 4000 Blacks “stood in line most of the day waiting to be voted.” The trouble started in Ocoee when Mose Norman arrived at the polls to cast his ballot. He was turned away because officials claimed he was not registered. In a tactic that was familiar in the South, the Justice of the Peace, R. C. Bigelow, who would hear voting appeals, had “gone fishing” and was not available to verify Norman’s registration. (Some sources claimed that Norman voted successfully early in the day and that it was July Perry who was denied the vote.)

Norman (or Perry) left the polling place and went to Orlando to consult with John Cheney.

Judge Cheney advised him to record the names of Blacks who were denied access to the ballot as well as the names of poll workers. The documentation could be used as evidence in future legal action.

When Norman (or Perry) returned to the polling place, accounts differ as to what occurred. Accounts seem to agree on two things: Norman stated, “I (we) will vote, by God!” and he was again denied the ballot.

Here the accounts vary widely. Some accounts claim that he brought a loaded gun into the polling place; other accounts state that the White men found a gun in Norman’s car, either clearly visible or under a shawl; a third account says Norman returned home, got his gun, and drove into town where he was confronted by Constable Bernie Cannon, who disarmed him and hit Norman with his revolver. Other accounts put the assault at the polling place.

Norman fled the scene to the home of his friend, July Perry, to relate the events of the day. Both men must have been aware that the escalation of violence enhanced the danger to themselves and the community.

Accounts also differ as to the formation of the first group of White men who confronted July Perry at this home. By one account, White men congregating around the local stores decided to confront Perry when they were informed that he was arming himself and others. A second story claimed that Deputy Sheriff Clyde Pounds (or Sheriff Frank Gordon) deputized 20 men to bring in Perry and Norman.

The ten men who went to Perry’s house were led by WWI veteran and former Orlando police chief, Sam Salisbury. They arrived at the Perry home sometime around 9:00 pm.

Vernon E. Parrish,“Bloodshed, The Price of History,” Term Paper (Bound), Spring Semester, 1949, P.K. Yonge Library of Florida History, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida.

Stories of what occurred at the Perry home are in general agreement. Salisbury called Perry to the porch, where they spoke briefly; Perry indicated that he needed to get his coat before leaving with Salisbury who grabbed Perry’s arm. Perry’s daughter, 22-year-old Coretha, pointed a rifle at Salisbury, who pushed the weapon away and the gun fired; Salisbury was shot in the arm.

Gunfire erupted between the Perry family inside the house and the men outside. In the course of the gunfight, both July and Coretha Perry were wounded, July Perry quite seriously, and two White men, Elmer McDaniels and Leo Borgard were killed as they attempted to enter the house from the rear. Men at the scene claimed that dozens of men were in the Perry house, but it seems that only the Perry family was inside.

When the men retreated, the Perry family used the time to escape. Perry’s wife helped him flee into the nearby cane fields; the two Perry sons hid in the barn; Coretha Perry stayed in the house to tend to her own serious, but non-life-threatening wound. A manhunt soon located Perry and he was arrested; his wife and daughter were taken into custody and transferred to Tampa.

Perry was treated for his wounds, which were viewed as likely fatal and moved to the Orange County jail under the custody of Sheriff Frank Gordon.

Alerted to the events taking place in Ocoee, some 50 carloads of men from surrounding areas descended on the town.

In the early morning hours of November 3, a mob arrived at the jail and seized Perry. They took him to a site near Lake Concord and the home of Judge Cheney. There they lynched him and riddled his body with bullets. No doubt the choice of site was intended as a warning to both Blacks who voted and Whites who encouraged them to cast ballots. Black undertaker, Edward Stone (some accounts say J.B. Stone), later removed the body and facilitated July Perry’s burial in an unmarked grave in the section of Greenwood Cemetery designated for Blacks.

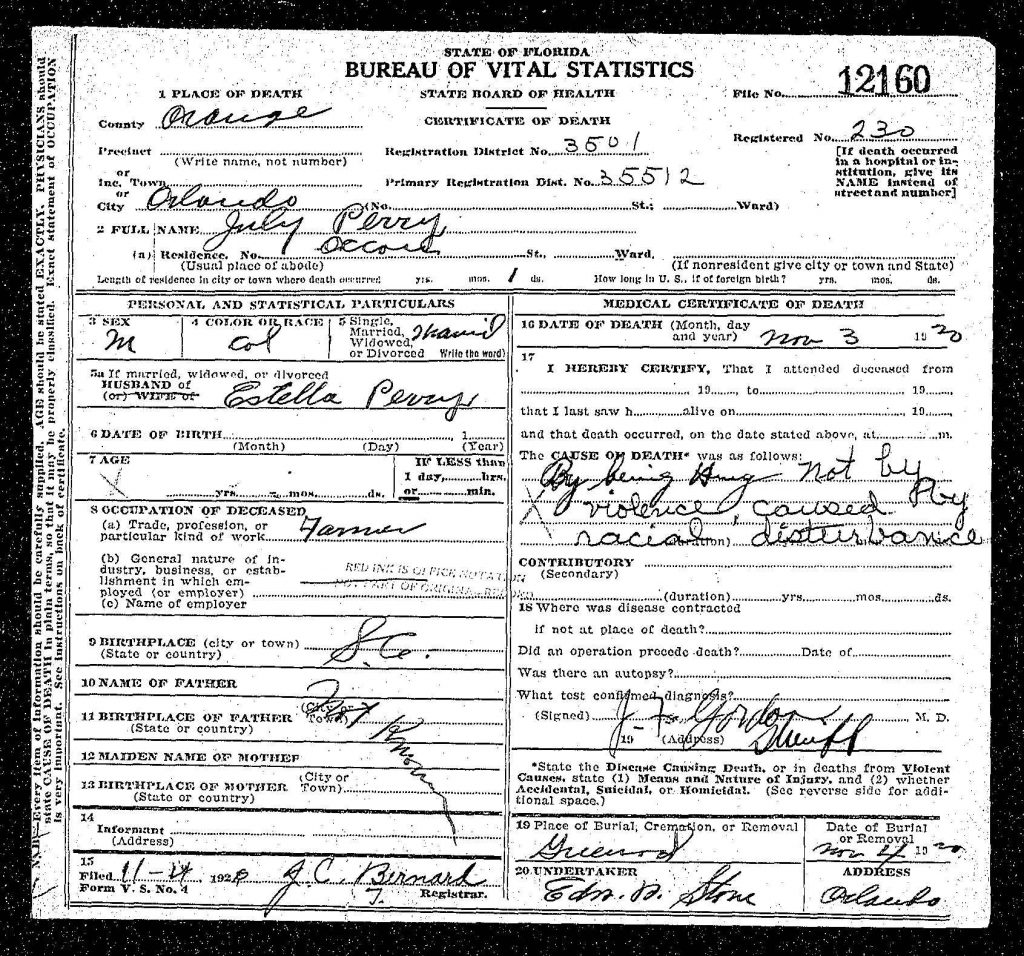

Death certificate for July Perry. His death certificate listed his cause of death as “By being hung.” And in different handwriting, “not by violence caused by racial disturbance.” (Image courtesy of the State of Florida.)

The Massacre

In Ocoee, the mob terrorized the Black citizens living in the Northern Quarters, setting houses aflame and trapping the people inside as they were caught between the flames inside and the gunfire outside. When the gunfire and arson ended, 25 houses, 2 churches, a school, and the Prince Hall Masonic Lodge had been destroyed. Residents of the Southern Quarters were warned that they should leave Ocoee or risk a similar fate. After 1921, only two Blacks remained in Ocoee.

Within the week, local stories about the violence divided into two separate accounts. What we might term the White accounts discounted what were deemed exaggerated levels of violence and defended the status quo of White supremacy. Black narratives focused on individual tales of violence against them and their escape. They also connected the violence to their legal exercise of the ballot, a connection that Whites increasingly discounted.

Black Interpretations of the Ocoee Massacre

Black understanding of the violence challenged the White version on every point.

-By November 5, 1920, Blacks and their White allies were placing the number of dead at 30, with most conceding that the total number of dead would remain unknown.

-The violence in Ocoee was perpetrated by Whites who sought to re-assert their control over Black social, economic, and political lives.

-Blacks saw the “home guard” as members of the KKK.

-Blacks recognized their determination to exercise their constitutional right to the ballot was a trigger to the subsequent violence. They made that argument to the U.S. Attorney General and before a congressional committee.

The Hightower Family

The Hightowers, like the other Black families in Ocoee, suffered terror, trauma, and property loss on the night of November 2, 1920 and in the days that followed. The youngest Hightower child, Armstrong, only thirteen at the time, recalled seeing the Perry family’s barn go up in flames as he and his siblings hid in the orange groves behind their house. The Hightowers left Ocoee almost immediately; there is no mention of them in the 1921 Orlando City Directory. They were forced to sell their land, almost forty acres, for much less than its value. The Hightower family reached safety by fleeing south to Fort Lauderdale.

The John Hickey Family

During the violent events of Election Day 1920, the Hickey family hid in the swamps in stump holes until the massacre was over. They emerged to find their home, along with many of their neighbors’ homes, burned to the ground. John Hickey found some of the family livestock, hooked up a wagon to the mules, and sent Lucy Hickey and the children through the back roads at night to Apopka, where they had friends who offered them shelter. Hoping they would have a better chance of surviving without him if they were stopped, John Hickey traveled through the woods and swamps at night to join them. The family was indeed stopped by White men on horses but were allowed to continue their journey.

The Hamiter Family

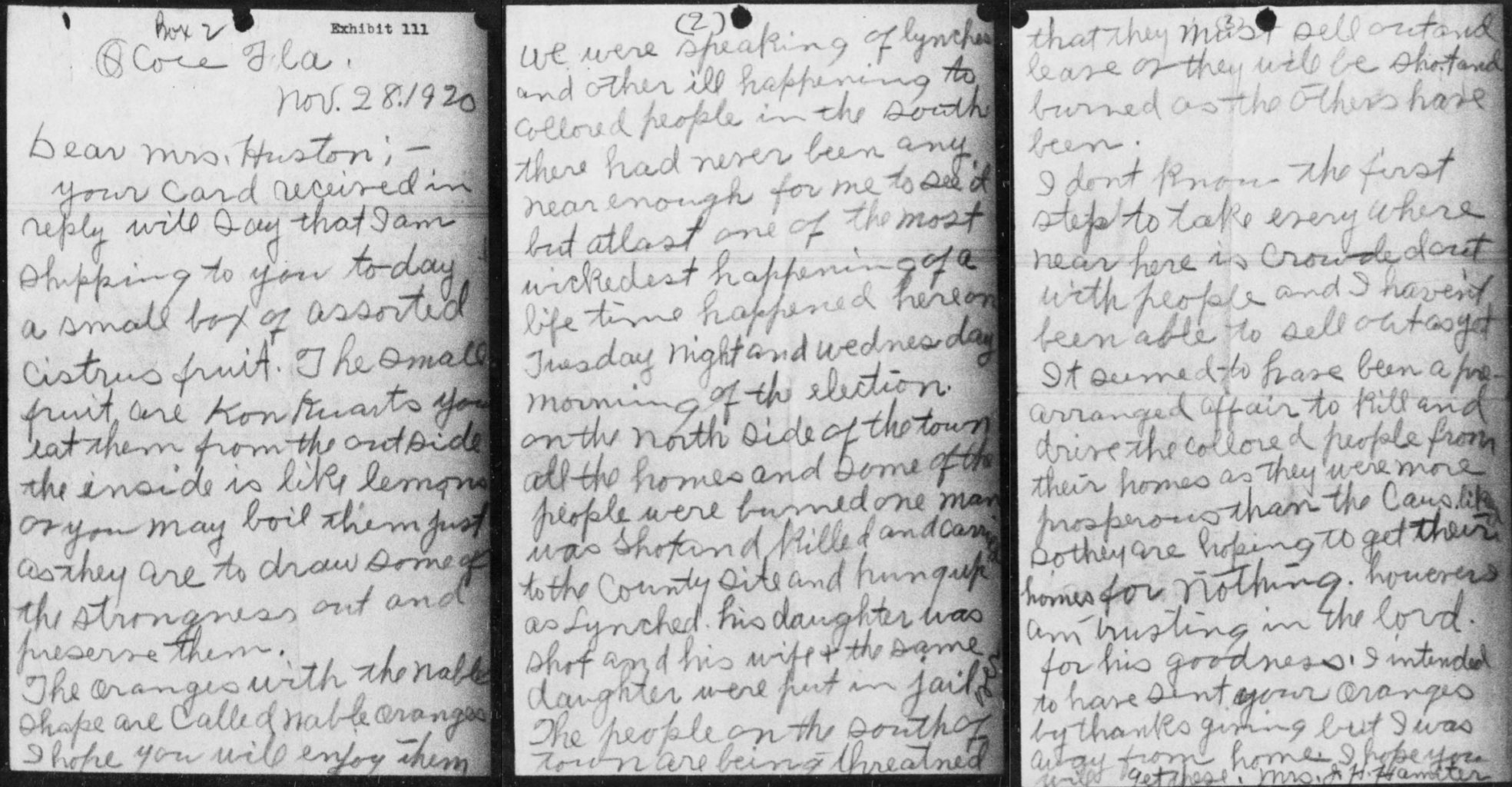

Annie Hamiter to Mrs. Huston, November 28, 1920. Collections of the Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

Ocoee, Florida

November 28, 1920.

Dear Mrs. Huston:

Your card received in reply will say that I am shipping to you today a small box of assorted citrus fruit. The small fruit are [kumquats] you eat them from the outside – the inside is like lemons to you may boil them just as they are to draw some of the strongness out and preserve them.

The oranges with the navel shape are called navel oranges. I hope you will enjoy them. We were speaking of lynches and other ill happening to colored people in the south. There had never been any near enough for me to see it, but at last one of the most wickedest happenings of a life time happened here on Tuesday night and Wednesday morning of the election. On the north side of the town all the homes and some of the people were burned, one man shot and killed and carried to the county seat and hung up as lynched. His daughter was shot and his wife and the same daughter were put in jail. The people on the south of town are being threatened that they must sell out and leave or they will be shot and burned as the others have been.

I don’t know the first step to take. Every where near here is crowded with people and I haven’t been able to see out as yet. It seemed to have been a pre-arranged affair to kill and drive the colored people from their homes as they were more prosperous than the white folks, so they are hoping to get their homes for nothing. However, I am trusting in the Lord for his goodness. I intended to have sent your oranges by Thanksgiving, but I was away from home. I hope you will get these.

(Signed) Mrs. J.H. Hamiter.

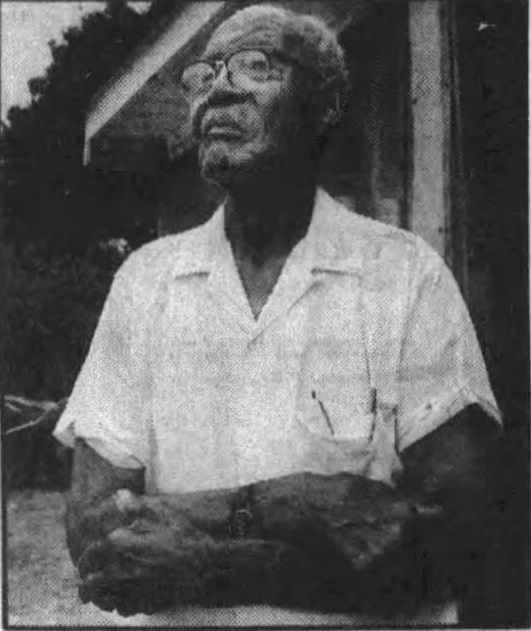

Richard Allen Franks

In 1986, Richard Allen Franks, age 84, described the night of terror for Orlando Sentinel reporter Bill Bonds. “They shot all night, ‘til sunup. Boom, boom, boom—like fireworks going off. Every time they set a house on fire a big blaze would go up. I hit out across the swamps. They came through the swamps and palmettos, looking for us like they were shooting rabbits.” Orlando Sentinel, September 7, 1986.

Coretha Perry Caldwell

“I never want to see Ocoee again, not even on a map.” -Coretha Perry

At age 87, Coretha Perry Caldwell recalled the gun battle at the home of her father, July Perry, on the night of November 2, 1920. “I heard my mama cry out, ‘They done shot my daughter…they done shot my daughter.’ I called to my mama, ‘Mama, Mama, I ain’t hurt. Get the children and crawl outside.’ …I told them not to run, because I thought they would be shot down.” Orlando Sentinel, September 7, 1986.

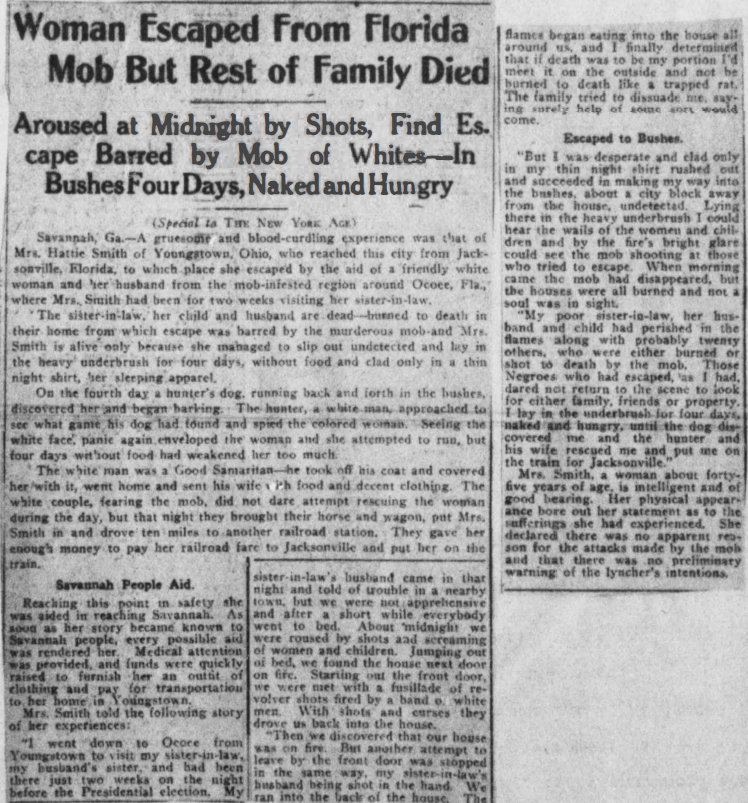

Mrs. Hattie Smith

This account was published in several newspapers, including the Dallas Express. Blacks and Whites related stories of White efforts to mitigate the violence and to assist in escapes. These stories are examples of what has been labeled as White paternalism.

Evelyn “Lena” Mann Wright

Evelyn “Lena” Mann Wright was 10 years old and living in Hannibal Square with her parents and siblings in November 1920. In an interview with Fairolyn Livingston at the Hannibal Square Heritage Center in 2011, Wright recalled the patrols by White men she described as Klansmen. The family home was near Fairbanks Avenue where the White men patrolled. Fearing a repeat of the attack on Ocoee, her father provided every child in the family of sufficient age with a gun for defense. He also moved the family to a home near the center of the Hannibal Square community for added protection.

The Black and White descriptions of the patrols were not necessarily contradictory. Membership in the KKK was widespread and included political figures, law enforcement, prominent businessmen, and church ministers as well as laborers and farmers. Klansmen sometimes marched without hoods and openly acknowledged their membership in the organization. Blacks would have known many Klansmen on sight and probably recognized some of the men on patrol as members of the Klan. Lester Dabbs noted that Sam Salisbury told him that 90% of law enforcement were members of the Klan.

Rev. Fred Louie Maxwell

Rev. Fred Louie Maxwell, who was age thirteen at the time, described his account of the massacre during an interview with Willie Clark for “Our Legacy: The Willie Clark Show Black History Special.” After discovering that July Perry had been shot, Mose Norman ended up at the Maxwell home in Apopka because he was “good friends” with Rev. Maxwell’s father.

White Interpretations of the Ocoee Massacre

The White narrative converged on four specific points.

-Six to eight people died in the “riot.” The use of the term “riot” suggests the use of violence was shared by both Blacks and Whites, rather than a massacre perpetrated by Whites on Blacks. Both White men and July Perry were named in the death totals, but the other Black deaths, which ranged from three to five were never identified by name in public accounts controlled by Whites. Failure to name the Black dead in newspaper stories and reports suggested that their lives and their suffering had no meaning beyond statistical accounting.

-Although fires raged through the Northern Quarters, the greatest destruction occurred when 5,000 to 8,000 rounds of ammunition stored in churches and homes exploded. This assertion suggested the loss of the homes and community institutions were the fault of Blacks, not Whites.

-Once the violence subsided, law enforcement and a “home guard” made up of White WWI veterans and members of the American Legion sealed off Ocoee and patrolled the streets of other towns in Orange County. Whites viewed this action positively as an example of the “best men” of the county re-establishing the “rightful order.”

-Initial news reports connected the violence to the election, but over time, Whites disconnected the two. They increasingly claimed that Florida’s election laws were fair, and since the violence occurred after the polls closed it had no connection to the election.

Alston, Lee J., and Joseph P. Ferrie. Southern Paternalism and the American Welfare State: Economics, Politics, and Institutions in the South, 1865-1965. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Apportionment of Representatives: Hearings before the United States Committee on the Census, 66th Congress, 3rd Session, on Dec. 28,29, 1920, Jan. 4-6, 1921, 71.

Dabbs, Lester, “A Report of the Circumstances and Events of the Race Riot on November 2, 1920 in Ocoee, Florida,” MA Thesis, Stetson University, 1969.

Orlando Sentinel, November 3-5, 1920.

Parrish, Vernon E., “Bloodshed, The Price of History,” Term Paper, Spring Semester, 1949, University of Florida.

Johnson, Guion Griffis. “Southern Paternalism toward Negroes after Emancipation.” The Journal of Southern History 23, no. 4 (Nov. 1957): 483-509. https://doi.org/10.2307/2954388.

“Paternalism.” Sociology. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://sociology.iresearchnet.com/sociology-of-race/paternalism/.

“The Ocoee Horror.” The Orlando Sentinel, November 6, 1920. From Newspapers.com.

“Woman Escaped from Florida Mob but Rest of Family Died.” New York Age, December 18, 1920. Investigative Reports of the Bureau of Investigation 1908-1922. National Archives.