Chapter 8: Aftermath of Ocoee

Header Image: Sundown Towns are white communities that exclude African Americans or other minority groups from being out in public after dark through laws and threats of violence. Although signs like these were once a part of American roadside culture, images of them are difficult to find. James Allen, who assembled an exhibit of lynching postcards, purchased this one around 1985.

(Image Courtesy of the Tubman African American Museum, Macon, Georgia.)

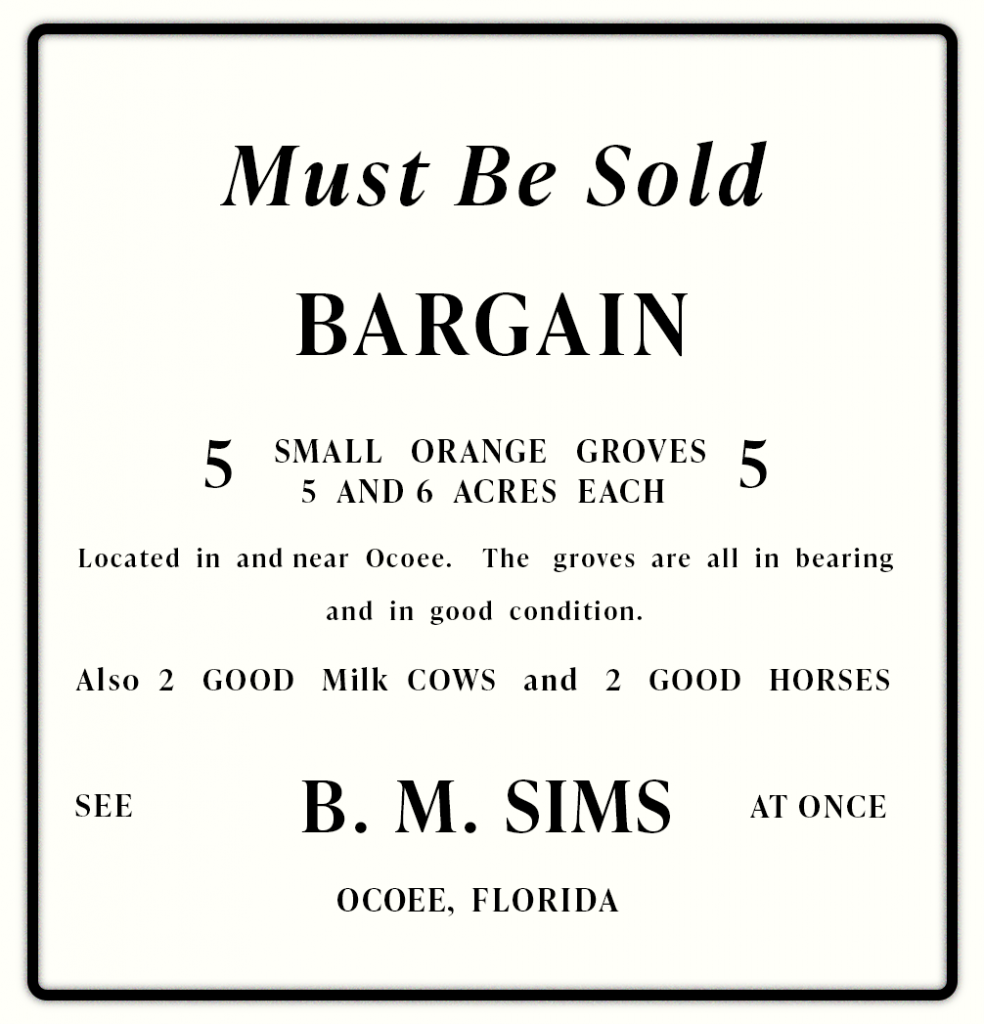

Migration out and Sale of Land

Black families remaining in Ocoee heeded the warnings they received and left the town. But, as Annie Hamiter’s letter indicates, the decision to abandon a lifetime of work with its accumulation of generational wealth was not taken lightly even under threat. “I don’t know the first step to take every where near here is crowded out with people and I haven’t been able to sell out as yet,” she wrote.

Sales of land brought pennies on the dollar. As Hamiter noted, “It [the Ocoee Massacre] seemed to have been a prearranged affair to kill and drive the collored [sic] people from their homes as they were more prosperous than the Caus. They are hoping to get their homes for nothing.” The NAACP transcript substituted “white folks” for “Caus.”

The sale of Black-owned land was underway by the end of the week of the violence. When Walter White arrived in Orlando on November 5, he was able to work undercover by claiming he was interested in the purchase of land in Ocoee. Bluford Sims handled many of the land sales, which also included farm animals in some cases.

Ocoee as a Sundown Town

By 1925, when Ocoee incorporated as a municipality, there were only two Blacks living within the city limits and by the time of the 1930 U.S. Census, none lived there. Ocoee became a sundown town, one of many such towns across the South and the United States. Sundown towns were the ultimate example of apartheid segregation, allowing no Blacks to be physically present inside the city limits after dark. The implied threat needed no clarification. Many Blacks living in Orange County today remember avoiding passing through Ocoee no matter the time of day.

The world’s only registry of sundown towns hosted by Tougaloo College (HBCU), Mississippi. Click on the map above. Following that link, users can click on a state, including Florida, to see an alphabetical list of all known sundown towns.

“‘There is no trouble here’: The Context of Ocoee in 1920.”

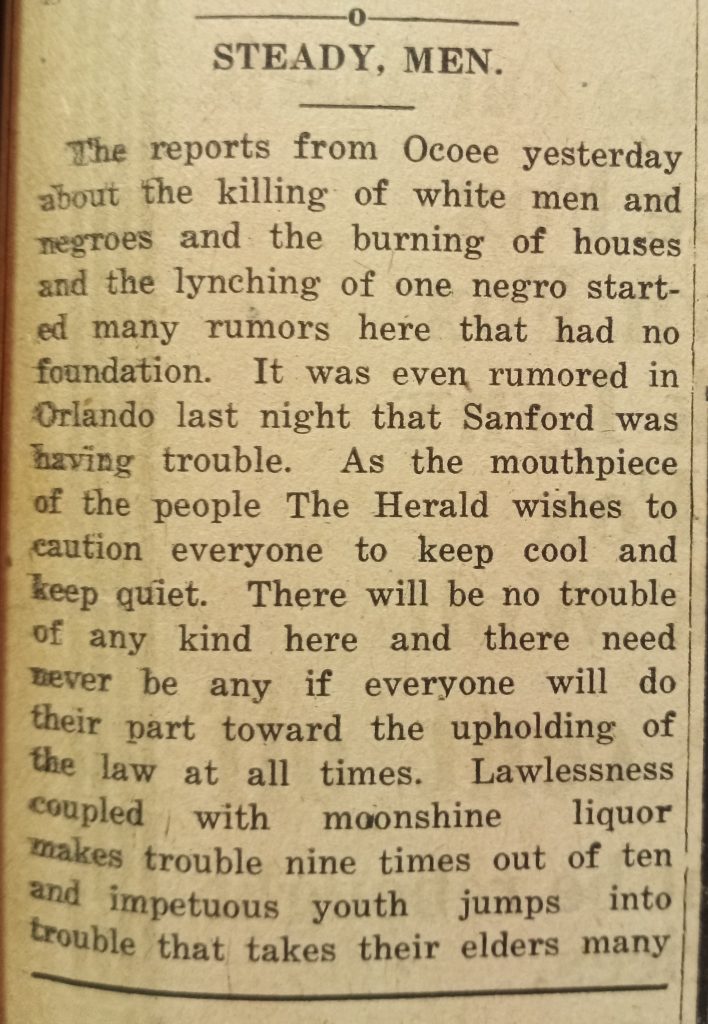

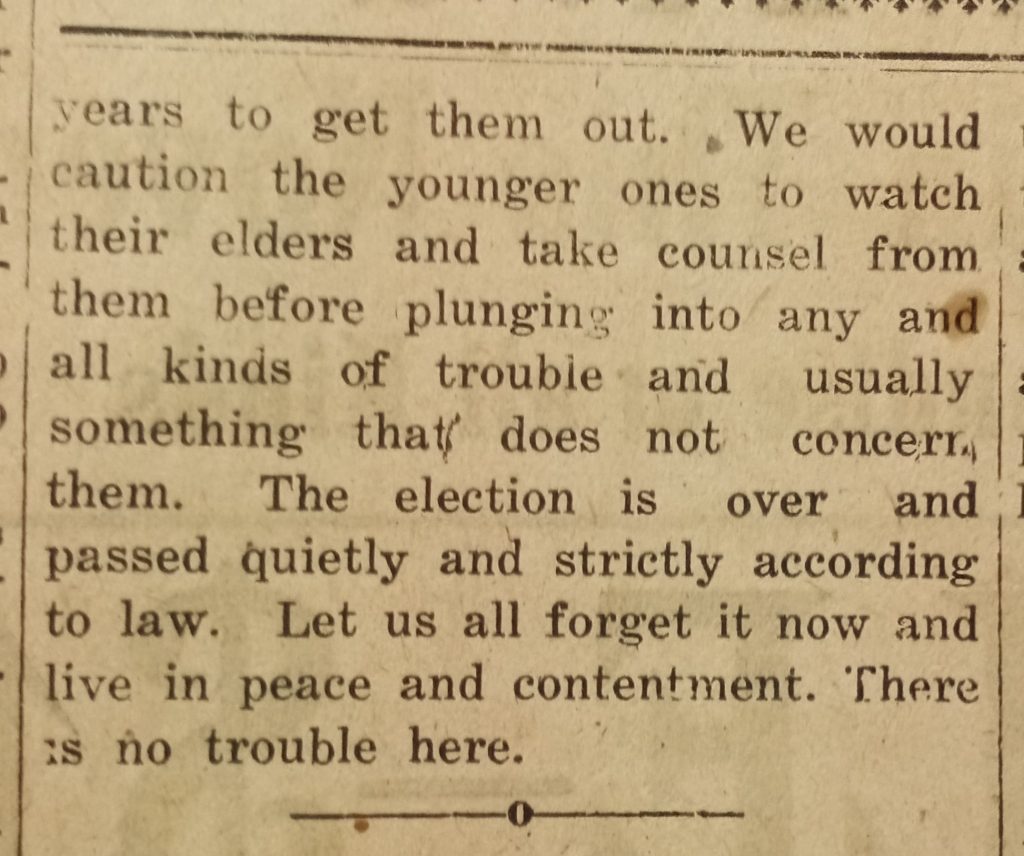

“Steady Men.” Sanford Herald, November 5, 1920, p. 4. (Courtesy of the Museum of Seminole County History.)

The Ocoee Massacre represented and maintained an American tradition of race hierarchy. Nineteen-twenty was a presidential election and census year. For the first time in the nation’s history, more Americans lived in urban, rather than rural, areas. The internal migration, mobility, and circulation by the beginning of the third decade of the twentieth century drew the color line of racial residential segregation in cities, towns, and suburbs. Indeed, spatial segregation was a hallmark of American life. The paradigm of White supremacy imposed on the landscape and inculcated in regional and national vernacular and representations rendered anti-Black violence legitimate, desirable, and normal.

The Sanford Daily Herald, published in Sanford, Florida, on Friday, November 5, 1920, three days after the Massacre, included an editorial entitled, “Steady, Men.” The single paragraph asserted, “The reports from Ocoee yesterday about the killing of [W]hite men and [N]egroes and the burning of houses and the lynching of one [N]egro” were rumors with “no foundation.” The editorial continued, “There will be no trouble of any kind here and there need never be any if everyone will do their part toward the upholding of the law at all times.” The article concluded: “The election is over and passed quietly and strictly according to law. Let us all forget it now and live in peace and contentment. There is no trouble here.”

The post-Great War era was marked by race riots during the Red Summer of 1919 and the Elaine, Arkansas Race Massacre in the same year, the Ocoee Massacre in 1920, the Tulsa, Oklahoma Race Massacre in 1921, the Rosewood, Florida Race Massacre in 1923, and at mid-decade, in 1925, the Ku Klux Klan paraded on Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C.

The public and private ethos of “there is no trouble here” dispossessed and murdered African Americans with impunity and disinherited them with a damnable reputation. The erasure of national, state, and local responsibility for the Ocoee Massacre was a repudiation of democracy and located Black Americans outside modernity and history. This is part of the context and meaning of the Ocoee Massacre.

“Steady, Men,” Sanford Daily Herald, Sanford, Florida, Vol. 1, No. 183, November 5, 1920, 4.

Other Digital Exhibits on Racially-Motivated Massacres

Tulsa Race Massacre (05-31-1921 to 06-01-1921) (The New York Times) (*Note: This exhibit is behind a paywall for subscribers.)

The Rosewood Massacre (01-01-1923) (Rosewood Heritage and VR Project)