Chapter 1: The Town of Ocoee

The town of Ocoee derived its name from Passiflora incarnata, which is a Cherokee name for the passion flower.

Approximately one-third of the population of Ocoee was Black in 1920. Black sharecroppers in Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina as well as the northern counties of Florida recognized the greater economic potential in Central Florida and migrated to the area. Hoping to not only find work, but to create inheritable wealth for future generations, they cleared land for others in order to acquire land of their own. After the events of November 1920, Ocoee became known as a Sundown Town, a place where Blacks could pass through but were prohibited within the city limits after dark. It became a place that erased Blacks and Black history from the landscape.

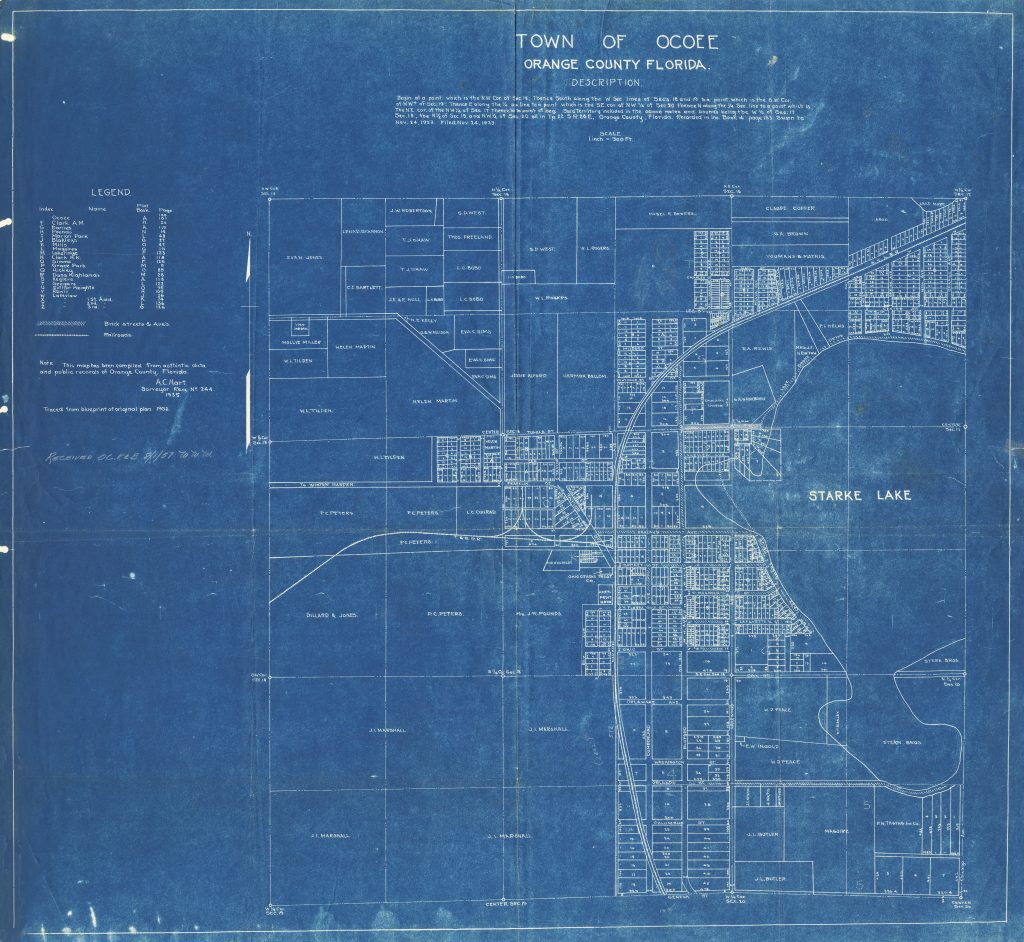

Mapping Ocoee

“The community was located in Voter Precinct 10 in West Orange County. No maps of Precinct 10 exist today; however, I believe the boundaries may have been [current street names] Windermere Road and Crown Point Road on the West, Fuller Cross Roads and Clarcona Ocoee Road on the North, Apopka-Vineland Road-State Road 435 on the East, and Robertson-Moore-Gotha Roads on the South. The area consisted of 28 sections of 640 acres per section for a total of 40,376 acres.” –James J. Fleming Sr, “Orange County Race Riot, November 2-3, 1920, Ocoee, Florida,” © 2003, courtesy Winter Garden Heritage Foundation.

(Image courtesy of Orange County Regional History Center.)

Population

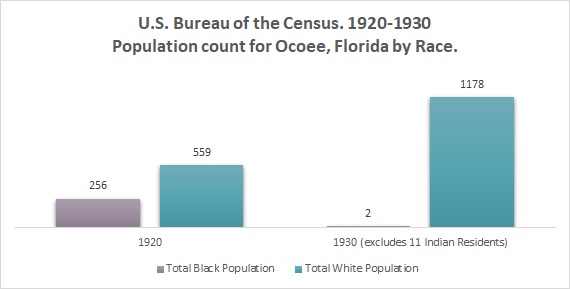

The population at Ocoee in 1920 numbered 256 Black Americans and 559 White Americans for a total of 815; Blacks were almost half the residents. By the next U.S. Census Bureau count in 1930, the number of White residents had doubled and the number of Black residents had fallen to two.

By 1920, twenty-two of the eighty-two Black Ocoee households lived in homes they owned. The 1920 U.S. Census listed 53 laborers, 15 farmhands, 13 farmers, 3 farm owners, and 2 washerwomen as heads of households; 14 respondents indicated that they were working on their own while 63 were wage laborers.

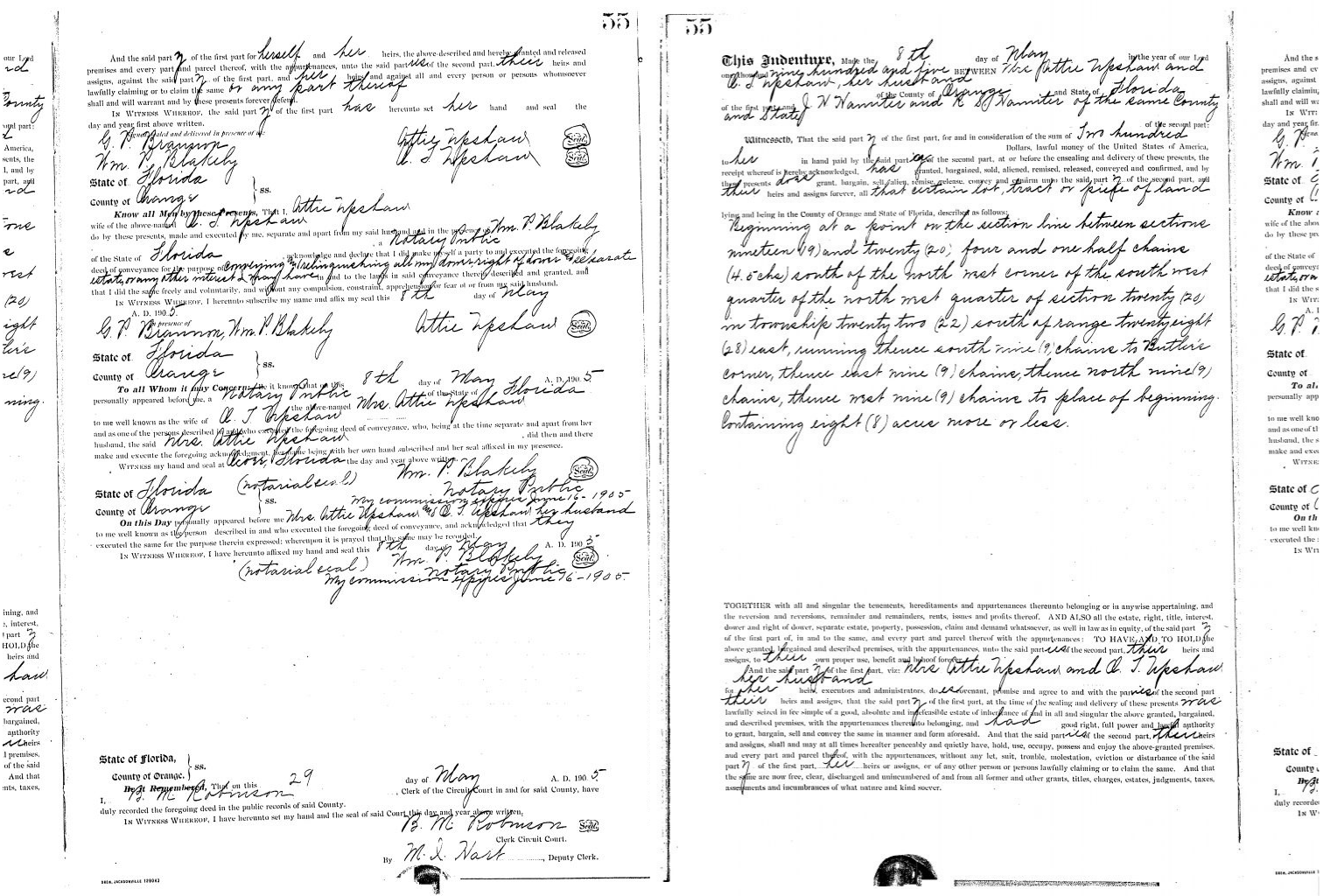

Land Deeds

Many Black sharecroppers in Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, and some of Florida’s northern counties migrated to Central Florida after discovering the greater economic potential in the area. Citrus proved more lucrative than cotton, which continued to dominate the southern agricultural market and made it an ideal crop for Black and White farmers with small landholdings. Upon arrival in Central Florida, many Black farmers cleared land for others in exchange for land of their own. This enabled them to build generational wealth. Unlike sharecroppers, who had no path to ownership over the land they worked, clearers were able to acquire inheritable wealth both through the value of the land itself and also as a result of the citrus groves and vegetable crops they planted. The Jack Hamiter family, who owned property in several locations in Central Florida, first acquired land as clearers. By the time of the 1920 Election, the Hamiters owned at least five properties in Ocoee, such as the one detailed in the deed above. In 1923, the Hamiter family sold this property for $5. Today, the property has an estimated value of at least $70,000.

The Cultural Landscape of Ocoee: Interpretation

The cultural landscape of Ocoee began with its founding as a rural antebellum community with an enslaved demographic and an enslaving White settlement. Slavery was part of the founding ethos of the state and nation. In the postbellum era, the emergence of modern Black America expanded American democracy and challenged the racial status quo. Dominant White Ocoee imposed race on the material environment and by analyzing the space occupied by Blacks and Whites, we can see how the organized and vernacular landscape of Ocoee reproduced racial hierarchy.

Businesses of Ocoee

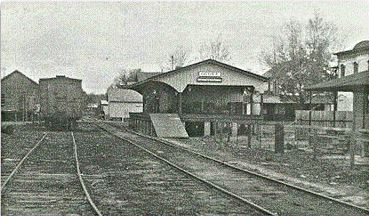

Railroad Depots

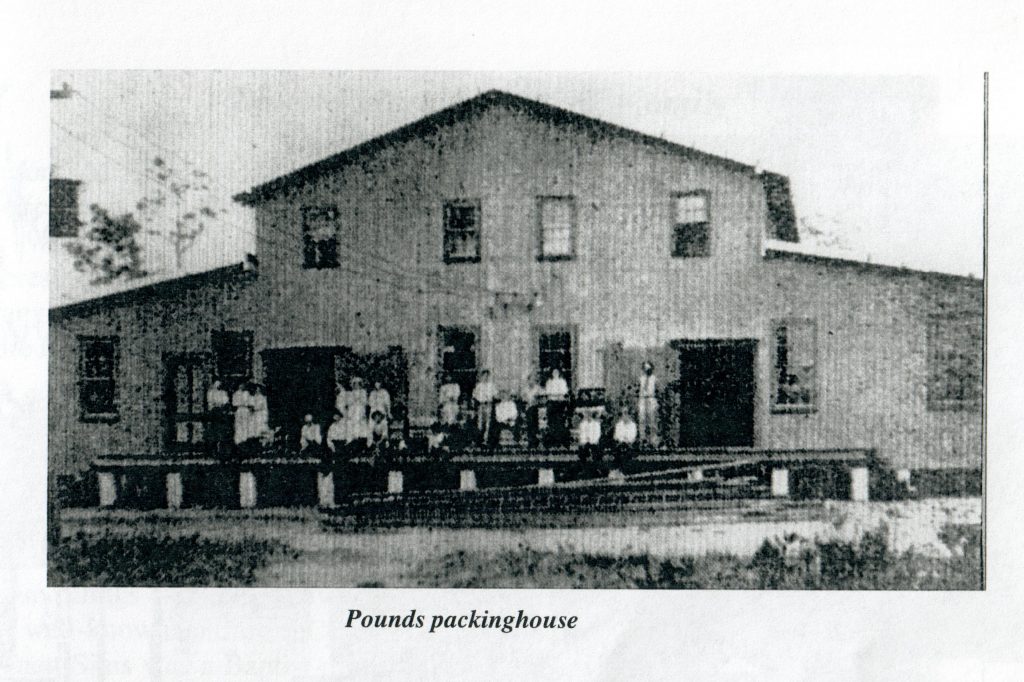

(Photo courtesy of the Winter Garden Heritage Foundation.)

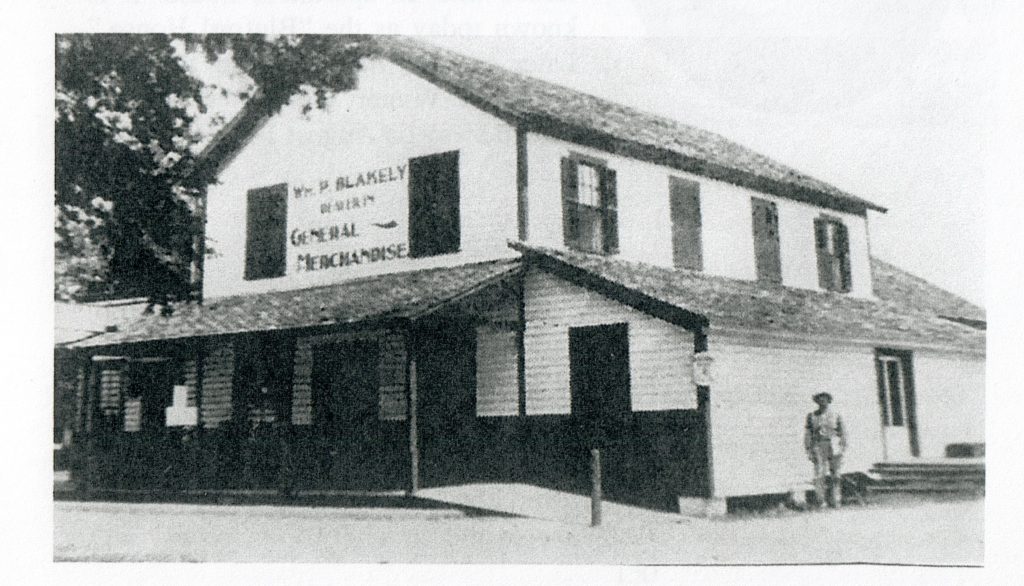

(Photo courtesy of the Winter Garden Heritage Foundation.)

Two rail lines served Ocoee, the Tavares & Gulf Railway and the Atlantic Coast Line/Midlands Railway Company. Access to rail transportation was essential to vegetable farmers and citrus growers who needed reliable service to buyers and refrigerated boxcars to ensure that their fruits and vegetables were consumer-ready. Packing houses were located near railroad lines to facilitate the loading of crates of oranges and grapefruit.

Railroads also served as important knowledge pipelines for the Black community. Black railroad workers brought newspapers from Chicago and New York and passed along information from near and distant towns. Annie Hamiter sent that important box of fruit with its letter to Corinna Huston on November 28, 1920 by rail informing her customer about the Ocoee Massacre.

Packing Houses

Like other parts of the South, the harvesting and processing of Florida crops followed racial patterns of segregated labor. Black workers harvested citrus and vegetables in groves and fields owned by Whites. A labor force that largely consisted of White women sorted and packed the fruit, and Black men loaded the crates of oranges and grapefruit onto refrigerated box cars. By 1920, packing houses in Central Florida were in transition from processing sites that resembled crude barns to modern buildings that utilized more efficient, mechanized processes that resembled factory assembly lines to prepare eye-appealing boxes of fruit for discerning consumers.

Ocoee Stores

In 1920 country stores were centers of commerce and social interaction. Farmers and their families came to country stores to purchase consumer goods and farming tools, sell garden produce, eggs, and home-made commodities, and interact socially. Country stores sold to both Black and White customers and the retail space was fraught with racial tension.

White customers congregated on the wide porches in good weather and gathered around pot-bellied stoves when conditions made the porches less inviting. Black customers were discouraged from congregating around the store and Whites complained if they perceived too many Blacks “hanging around” the porch and yard. Increasingly, merchants designated a day, usually Saturday, for Black customers to do their shopping.

Merchants also “carried” both Black and White customers on credit accounts until “settling time” when crops were sold. Buying on credit was expensive, but in cash-poor rural communities it was essential. Citing their financial risk, merchants marked up credit purchases 25%, 50%, or even 100% depending on the perceived credit worthiness of the customer, a perception that included race as a factor. At “settling time,” there was no appeal for the ledger balance and White merchants with Black customers often placed their White wives or daughters in charge of the accounts to prevent disputes over charges.

Black merchants catered to Black customers, but the size of their stores and variety of selections were usually smaller. Some stores were located in the front room of the owner’s residence. Valentine Hightower owned a small grocery business that catered to Black customers in Ocoee.

Carol Anderson, White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide. New York: Bloomsbury, 2016.

Edward L. Ayers, The Promise of the New South: Life After Reconstruction. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

W.E.B. DuBois, “The Negro Farmer,” in Negroes in the United States by William Chamberlain Hunt, Walter Francis Wilcox, and W.E.B. DuBois. Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1904.

Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution 1863-1877. New York: Harper & Row, 1988.

Charles E. Hall and Z. R. Pettet, Negro in the United States, 1920-1932. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1935.

James Andrew Padgett, “Rebuilt and Remade: The Florida Citrus Industry, 1909-1939.” MA Thesis, University of Central Florida. 2018.

Richard H. Schein, ed., Landscape and Race in the United States.New York and London: Routledge, 2006.